The purpose of war is to break the enemy’s will and to impose the will of the victorious nation on it. Occupying the enemy’s country and removing from authority its government to seize control of the foe’s sources of wealth and power has always been an effective method to realize this.

But this is not an easy feat. The adversary is almost surely going to oppose such adventure through the force of arms.

The aggressor needs to apply force over the target country to attain its purpose.

If diplomatic efforts, economic pressure, and/or domestic incited strife are not sufficient or are deemed too slow to achieve the expected result, the military force needs to be utilized.

But how should this force be applied for maximum effect?

The Great War showed that the classical approach of defeating the opposing armed forces by utilizing land armies was still a practical way of doing business, but the cost was appalling in blood and treasure.

Giulio Douhet, an Italian General and air power theorist, proposed a radically different approach of force-application. His theory propounded the unrestricted bombing of enemy cities by air armies to kill and maim civilians and leaving them homeless. Under such tremendous pressure, Douhet insisted, the civilians would find it impossible to bear the stress and they would direct their anger towards their government forcing it to capitulate.

This doctrine of an aerial attack on civilians to kill and terrorize them was (rather unsuitably) christened “strategic bombing”.

The British RAF and American USAAF became the strongest tangible advocates (if not necessarily willingly supporters) of this theory during World War Two.

The RAF leaned towards this doctrine with an unbending focus. The British harnessed immense technological, economic, and military resources to make it succeed.

While they eventually killed many civilians and caused immense destruction on German cities the RAF, itself suffering a terrible mauling, failed to force their adversary to surrender by an ample margin. Despite this failure, they became convinced that their approach was correct .

The American USAAF also encouraged bombing civilians, but their approach differed markedly from the RAF and Douhet’s. Instead of unrestricted attacks against the German communities as a whole, to “break their morale”, the American centered their bombing efforts on industrial targets where civilians produced the means for sustaining their country’s war effort, like factories and oil refineries. It should be noted that for the Americans, children and old people were not an intended target but collateral damage .

The British quickly learned that their bombers could not survive in the heavily defended skies over Germany, so they switched to night bombing. The American approach, requiring daylight attacks to identify the targets, proved more effective, forcing the Germans to devote more resources to defend against this threat.

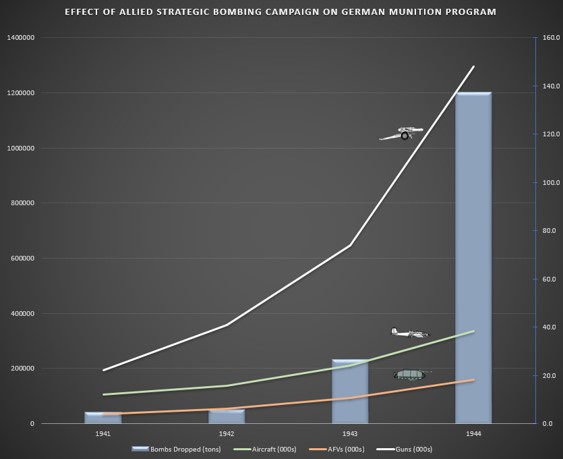

However, the round-the-clock bombing campaign failed to dislodge the German munition industry.

On the contrary, German weaponry output continued to grow inexorably until the very end despite the order-of-magnitude increase of the allied bombing effort (see next image).

Despite this evidence, western literature ruled the “strategic” bombing doctrine as superior to the use of an air force in support of the army.

But was this the case?

The German Luftwaffe operational doctrine published under the aegis of the Chief of Staff, General Walter Wever as Air Field Manual 16, placed the mission of the air arm on the application of force on the enemy’s military forces in support of the army (and navy, when necessary). Only when certain conditions were present (i.e. stalemate) would the priority change to attack the enemy’s industrial centers .

This mission has been defined as “tactical” by the Americans and British air theorist, implying that it is an inferior approach to win a war . Most historians have jumped to the same wagon it appears.

Nonetheless, the historical record shows that the Luftwaffe was more successful than its counterparts in breaking the enemy’s will.

By using a tactical air force, the Germans achieved strategic results in battles lasting a few weeks: they forced the complete defeat of Poland, Norway, Yugoslavia, Greece, Belgium, the Netherlands, and the biggest prize of them all, France.

Conversely, by using “strategic” air forces, the British and Americans, after costly, hard-fought campaigns, lasting years, only achieved tactical outcomes: they forced the Germans to better defend themselves by utilizing resources better used elsewhere. The USAAF can also receive credit for defeating the German day-fighter force after a long-drawn-out period.

Why this difference?

While in theory, the bombing of manufacturing plants reduced output, in practice Germany, Great Britain and the United States found out that this was a very complex problem. It required precise intelligence to establish the location of the industrial centers, their output, relative importance, construction materials, and layout of the factories to plan an effective attack. Then it necessitated adequate weather to enable visual bombing , a distance to target within the range of the bombers, and a remarkable bombing accuracy with suitable bombs, in sufficient quantities to destroy them.

And even if the bombers hit the factories hard, stocks cushioned the impact in the short term and the plants could be repaired relatively quickly, resuming production much faster than initially thought possible. Consequently, the bombers needed to repeat periodically the attacks on those factories, and this could only be done if the losses were acceptable.

For most of the war, the German fighter force inflicted prohibitive losses on the allied bombers attacking crucial targets deep in Germany, thus preventing them to return fast enough. The effect was the tardiness of “strategic” bombing to show results: it was until mid-1943 that the RAF and the USAAF succeeded in seriously damaging some important German targets .

It was only after the USAAF defeated the Jagdwaffe that the American bombers were at last, able to survive in sufficient numbers to allow them repeating attacks .

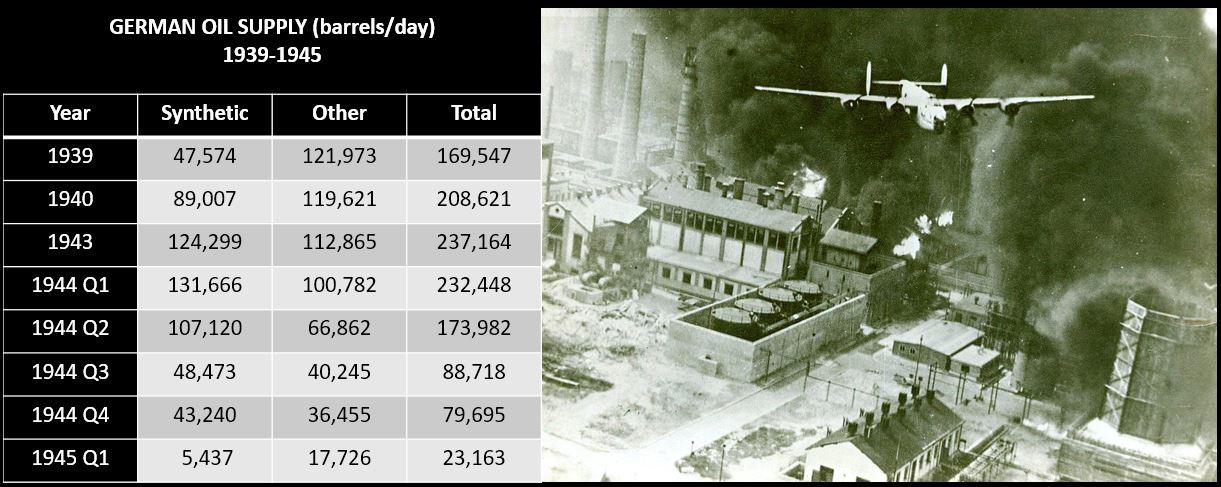

This victory took a long time: 17 months from January 1943 to the second quarter of 1944 when the bombers were finally able to seriously affect the German war machine by partially destroying their oil refineries (see next table) . Another 3 months (Q3 1944) of intense bombing prompted on the Wehrmacht a severe crisis. The American air force succeeded in devastating the oil industry , but it did not force the German army to surrender.

By that time, the Soviets had been on the strategic offensive for one year already and had evicted the German army from their country, soundly defeating it.

In contrast, the Luftwaffe saw that the defeat of the enemy army brings about complete victory. Airpower could degrade the enemy’s army capability by preventing the troops from receiving supplies. This could be accomplished not only by destroying the factories but by blocking the supplies from reaching the troops .

The latter was possible by interdicting railroad and road communications: bombing supply trains and road convoys on the march and/or bridges, tunnels, cities, and other infrastructure that caused the columns to stop . These attack methods inhibited the transportation of provisions and the delivery of reinforcements to the engaged armies.

The impact was swift because these supplies were needed at that time, and the lack of them caused the enemy’s armies to become notoriously brittle. Without food, oil, ammo, and replacements it was unfeasible to continue the fight.

An additional advantage of tactical bombing is that it required less intelligence to identify key targets. Supply routes are very visible from the air, whereas camouflaged factories deep in the enemy territory along with the plethora of other variables necessary for successful attack entailed more diligent intelligence work.

Finally, by facilitating the task of the army, ground troops could advance and capture the enemy factories for good, eliminating them from the equation altogether .

Evidence is clear: the Luftwaffe success as a tactical air force was unprecedented and decisive. It was only when the German leaders committed the Luftwaffe to a multi-front war, that this legendary air force was extended beyond its capabilities, simply because its force structure was insufficient.

When Germany invaded the Soviet Union, the Luftwaffe was simultaneously fighting wars in the west, defending the continent and Germany proper, and in the extensive Mediterranean Theater. The Luftwaffe head of operations, General Otto Hoffmann von Waldau recognized this strategic mistake immediately and warned the Luftwaffe Chief of Staff Hans Jeschonnek to no avail .

Many historians blame the Luftwaffe leaders’ lack of vision by claiming that they should have developed a “strategic” air force and had they done so, the USSR would have been soundly beaten. This theory, advanced without any quantitative evidence, is mistaken. A detailed analysis of this hypothesis can be found in the “Factories” section of the chapter devoted to strategic reserves.

Suffice to say that the ability of the United States and Great Britain to raise enormous strategic bomber forces was possible at the expense of the size of their land armies. Despite a combined population much larger than Germany, they deployed considerably fewer divisions than the Wehrmacht. The Soviet Union, forced to defend a huge frontier, placed its weight in the land army and never developed a strategic air force. Germany’s economic and raw material restrictions did not allow it to build an air force with the size to wield simultaneously tactical and strategic campaigns while maintaining a large land army.

The leaders had to select carefully where to place the priority because compromise measures would have been worse.

A force of 400 “strategic” bombers would not have undermined the Soviet industry, while the resulting reduction of the tactical bomber force to half the size it had in 1941 meant that the swift strategic victories over its opponents, achieved during the first 2 years of war, would have been beyond its grasp. Lack of a striking bombing force capable of interdicting enemy rear areas signified that a vital component of the Blitzkrieg would be missing, seriously endangering the advance of the armored spearheads. The deep penetrations would not have been successful .

Historic facts show that the Heer was not able to attain any major offensive victory during WW2 without air superiority and air support.

Had a “strategic” bomber force of 900 heavy bombers been available (about the largest size it could get if the tactical bomber force was eliminated), it would have been insufficient to defeat France and Great Britain quickly, forcing Germany to wage a long-protracted war against its western enemies, thus preventing it from invading the Soviet Union.

The German decision to develop a tactical air arm was the correct one.