!

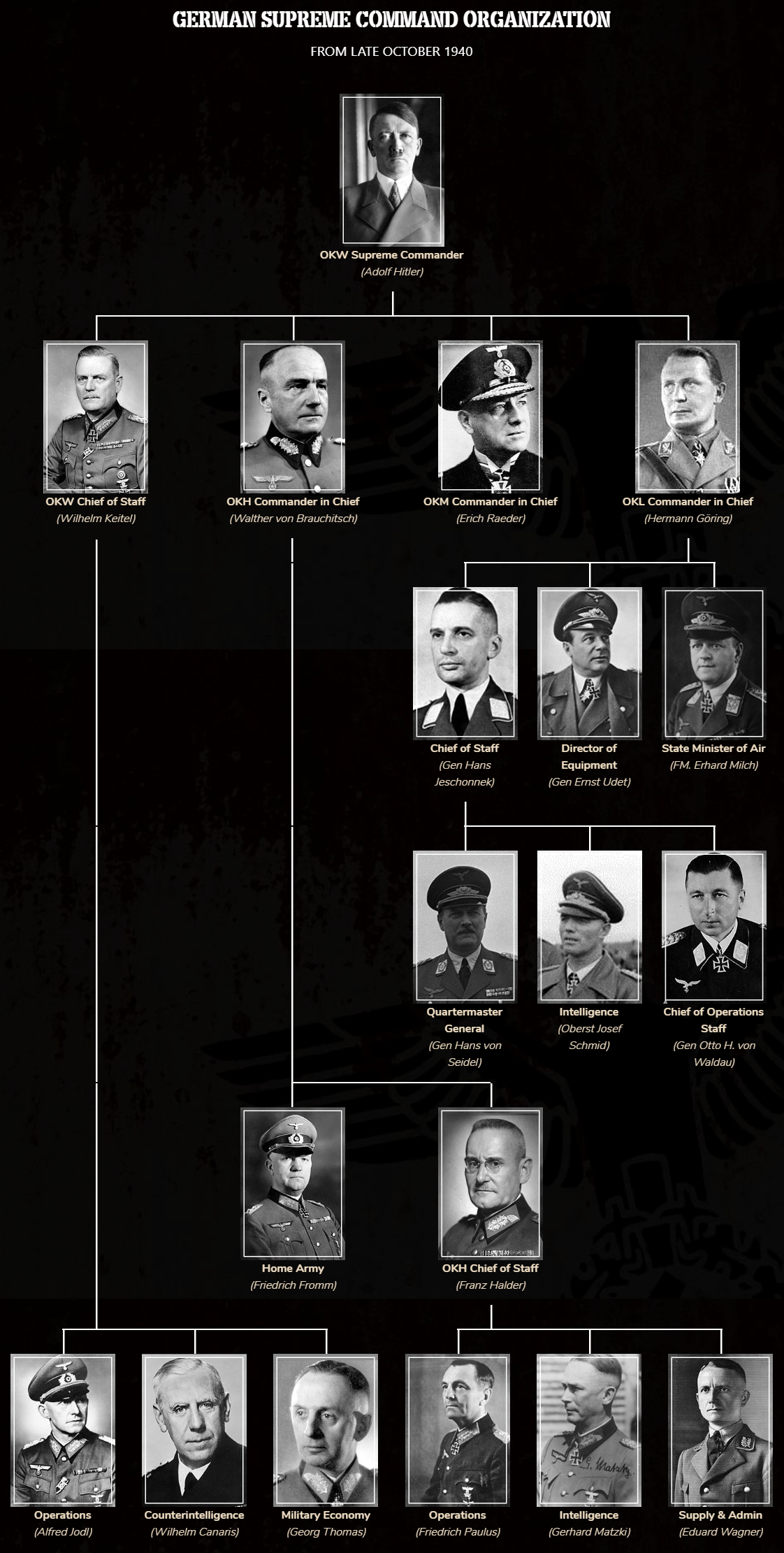

The Oberkommando des Heeres (German Army High Command) was subordinated to the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (Supreme Command of the Armed Forces)

In early September 1940, General der Artillerie Alfred Jodl, Chief of the Operations Department in the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (OKW), ordered Generalmajor Walter Warlimont, his deputy, to prepare an independent plan for the invasion of Russia. Jodl, wisely, sought an unprejudiced perspective to advise Hitler once the Army plan arrived at the dictator’s desk . On 19 September, Warlimont submitted it to Jodl. Regrettably, the new plan differed from Marcks’s only in operational detail because it was still based on the same premises of Russia’s strength provided by Kinzel.

Warlimont’s plan (OKW plan) proposed three army groups instead of the two suggested by Marcks. Both plans envisaged three main axes of advance: towards Leningrad, Moscow, and Kiev, but Jodl preferred one army group coordinating independently each attack for better mission control. Equally, Warlimont agreed to locate the center of gravity north of the Pripet Marshes. However, the OKW plan envisioned that if the northern army group was not powerful enough to capture Leningrad and to destroy the Soviet forces in the Baltic, the army group to its right would pivot to the north and help it to complete its task, before resuming the advance on Moscow. This was an important operational difference, although hardly a strategic one.

The OKW plan reveals that for the second time, the planners concluded that a rapid victory over the Soviet Union was within the means of the German Army.

Had the OKH and the OKW built a solid case indicating that the size of the Russian Army prevented victory in a lighting campaign and therefore, the German leadership should prepare for a protracted war, it is quite likely that Hitler would have pondered cautiously the next move, even to the point of rejecting the invasion. After all, Hitler’s requirement that Barbarossa launching was contingent on the ability to defeat Russia in a short summer campaign, was fundamental in his eyes .

At this stage of the war, The German High Command judgment had a satisfactory weight with the dictator if backed up with solid arguments. Its opinion was more important than that of the OKM or OKL as will be explained later.

Evidence of this clout is demonstrated when weeks earlier Keitel convinced Hitler that an invasion in 1940 was not possible because the Polish road and rail networks were insufficient to permit the assembly of strong-enough forces in time, even though the dictator contemplated this course of action.

Nevertheless, the OKW optimism did not cause Hitler to make an irrevocable decision yet. Its purpose was merely to provide feedback to the OKH’s plan.

Many historians have argued for years that the OKW’s plan spoiled the Army’s concept (implicitly stating that the latter was the better plan) because it influenced Hitler in his decision not to go straight for Moscow, but evidence strongly suggests that neither the OKH nor the OKW concepts would have brought victory to Germany .

If Kinzel’s estimate of the Red Army’s strength had been correct, both plans were equally capable of bringing triumph to the German arms. During the actual campaign, utilizing the (modified) OKW’s concept, the German Army destroyed 229 Soviet divisions between 22 June and 31 December 1941 , much more than Kinzel’s estimate of the total Red Army strength (202 divisions). Had the Soviet army not possessed the reinforcement capability that in fact, it enjoyed, the utter defeat of the USSR was a certainty.

On the other hand, neither of the two plans appear to be drastically better than the other for facing the actual strength the Soviets threw at the Germans. The evident replacement disadvantage of the German army is so blatant that had the Germans used the OKH plan instead, their offensive would still have bogged down in the face of insufficient resources and time just as the OKW plan did.

Declaring, like most historians, that the Wehrmacht would have attained victory by adhering to the OKH’s original plan is speculation. It is habitually offered without any supportive evidence except for subjective opinions. The opposing stance, that following the OKH plan would not have brought victory is speculation too.

However, we can do better than that by wargaming both scenarios many times and identifying if following one plan is clearly better than the other.

Wargaming a German offensive against the planned Russian strength shows that German victory is highly probable irrespective of which plan is used . This (simulated) result agrees with the historical fact that the German army destroyed in 1941 more divisions than what it planned to face.

However, wargaming Barbarossa against the actual Russian strength shows that the probability of a German victory in 1941 was only about 6% . A quantitative analysis by the author also corroborates the hypothesis that the odds of winning in 1941 were remote, even if the Germans had marched to Moscow after Smolensk . The weight of the Soviet reinforcements is telling.

A few weeks after Marcks submitted his plan to the OKH, while Warlimont was busy preparing his own, Franz Halder appointed General Friedrich Paulus to lead O Qu I (Operations) and assigned him the task to develop Marcks’s strategic concept into an operational blueprint. He immediately started to work on a survey of Marcks’s design to corroborate its feasibility and to delineate operational solutions to any detected problems.

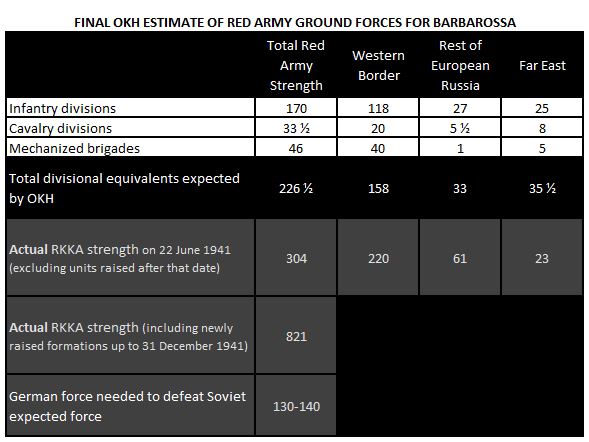

Paulus worried about the repercussions on Germany’s fortunes if Kinzel’s intelligence estimate was incorrect. This skeptical posture was prudent, but his follow-up action was feeble at best. Rather than assertively poking holes at Kinzel’s assessment, he limited himself to adding 10% more division to the appraisal of O Qu IV (from 202 to 226 divisions). When he incorporated this modest increase into his wargaming the General found that defeating the Soviets before the winter became very challenging. Since the muddy season in Russia begins by mid-October, Paulus realized that this addition to the Red Army’s order of battle would translate into an enormous pressure on the Wehrmacht to destroy the Soviet forces in the very short timeframe available (the larger the enemy force, the longer the time it takes to destroy it). However, he considered that German qualitative superiority in mobile operations would just make this possible.

It is evident that if he had augmented the Soviet reinforcement capability by 300% (the actual figure), his conclusion would have been that a multi-year campaign would be necessary to defeat Russia. The Wehrmacht lacked the resources to win the campaign within 5 months in the face of the colossal size of the enemy’s army .

Had Paulus utilized an estimate only 50% higher than Kinzel’s, he would likely have concluded that there was not enough time to defeat the Red Army in a short summer campaign. Unfortunately for Germany, lacking supporting data, he did not press the matter further. At the very least, he should have estimated the strength of the Red Army that prevented victory before the muddy season to assess the risks and inform his superiors.

Paulus and therefore OKH’s, final estimate of the magnitude of the Red Army strength remained woefully inadequate and divorced from reality. Equally ineffective were the projections of the Red Army’s air force strength set at 8.000 aircraft, of which 6.000 (75%) were in European Russia . In reality, 19.649 aircraft were on-hand with the VVS on 22 June 1941 of which 11.425 were in the border districts .

The magnitude of these errors (300% in the size of the Red Army and almost 100% in the size of the VVS) meant that from this point on, only the best possible set of circumstances could help the Wehrmacht to accomplish its task .

During the next two months, he organized intense exercises and wargames that culminated in the formulation of a preliminary plan of operations tendered to Halder on 29 October 1940.

This plan confirmed that the campaign would bring victory in the allowable time and that the Moscow axis was the best choice for the main effort. This would be the third time that the German Army reached the same optimistic outcome (the other two were the proposals of Marcks and Warlimont).

On that date, at the latest, the principal individuals in the German Army (Marcks and Paulus, Halder and von Brauchitsch) and in the OKW (Warlimont and Jodl) agreed that a lightning war against the Soviet Union would be successful.

The refinement of the OKH’s plan continued unabated. An enormous number of man-hours was ahead of Paulus to polish every detail of the design. He attempted not to leave anything to chance (with the major exception of the all-important premise of the enemy’s strength). Between November and mid-December, a very thorough series of map exercises and wargames carried out concurrently by both, the OKH’s O Qu I and the chiefs of staff of the armies and army groups earmarked for the invasion, culminated with a conference in the Army headquarters on December 13 and 14.

The outcome of this conference, chaired by von Brauchitsch and Halder is extremely relevant because, despite several problems identified during the exercises, the general conclusion was that the Wehrmacht would defeat the Red Army in a campaign lasting no more than 8 to 10 weeks.

Although there is no concrete evidence to suggest that the German Army was consciously attempting to fool Hitler into believing that Russia was ripe for defeat through a lighting campaign, in practical terms the generals deceived themselves, and thus, they deceived their commander in Chief .

The optimism of the German army’s field and staff commanders was widespread. All the high-ranking ground army experts coincided with this , irrespective of what transpired later. This belief had its justification in many factors that appeared reasonable without hindsight: The deficient performance of the Red Army against Finland, the recent purges of the Soviet army commanders, the disaffection of the population with the communist regime, the expectation that the Russian army was inferior to the French army, and an overall sense of superiority on the capabilities of the Wehrmacht and its blitzkrieg methods. Equally important, based on the historical industrial backwardness of Russia, demonstrated in the last World War, they could not fathom a Soviet Army larger than the one Kinzel projected .

On 5 December, even while the Heer wargames were still on-going, von Brauchitsch and Halder made a verbal presentation to Hitler based on Paulus’s preliminary plan of 29 October . The Fuehrer accepted the assumptions and conclusions of this plan, including the decision to place the point of main effort to the North of the Pripet marshes and the strength the German army required to accomplish the defeat of the Soviet Union (fixed at 130-140 divisions).

Hitler emphasized the need to destroy as many Soviet units as close to the border as possible and his opinion that Moscow was not extremely relevant. Therefore, he did not want to commit himself to attack the capital until the army eliminated the projected northern and southern pockets. These pockets were likely to develop because Army Group Center would initially have the bulk of the armor and Luftwaffe support and thence it would gain ground faster than the adjoining army groups. Since the objective of the campaign was the destruction of the Red Army, it made sense to destroy these vulnerable forces first (vulnerable because they would find German forces behind their front). He would decide the next step based on existing conditions on the ground when that happened.

Neither the Commander in Chief of the army nor his Chief of Staff presented any objections because they perceived this as non-critical. They expected that by that time, the German forces would have destroyed the bulk of the Russian army, and it would be obvious that the advance on Moscow could proceed.

The widespread optimism in the ground army circles contrasted vividly with the apprehension in the Navy (Kriegsmarine) and in the Air Force (Luftwaffe). The supreme commanders of both branches, Admiral Erich Raeder, and Field Marshal Herman Goering, respectively, attempted vehemently to dissuade Hitler from attacking the Soviet Union until after the defeat of Great Britain.

Admiral Raeder first approached Hitler on 26 September 1940 and suggested to support the Italian attempts to seize the Suez Canal and follow up with an advance across Palestine and Syria. Besides the considerable impact that the losses of oil and the Eastern Mediterranean positions would have on the British empire, Turkey would become vulnerable and therefore agreeable to the new world order. He insisted that the Soviet Union was not an immediate danger because it was afraid of Germany’s power.

Hitler approved Raeder’s ideas and coincided with the Admiral’s opinion that Russia was afraid of Germany. He added that the Soviet Union should be tempted to turn towards Persia and India to gain access to the open sea . By doing so, there would not be a cause of conflict between Germany and Russia (because both countries would be expanding towards the south and not towards each other borders ) and no possibility of an agreement between London and Moscow (because Russia would be participating in the destruction of the British Empire).

At around that time, Field Marshal Goering also presented objections to the interruption of the air war against Britain that the new conflict would bring about and proposed a similar course of action as Raeder’s . Several Luftwaffe top commanders, besides Goring, opposed the new war. General Otto Hoffmann von Waldau heading the Luftwaffe operations department and General Hans-Georg von Seidel, the Luftwaffe Quartermaster General, both indicated that a multi-front war was beyond the Luftwaffe capabilities .

Hitler, who at the time was attentively listening to the different points of view, could perceive the risks that the new war implied and the advantages of reaching an agreement with Stalin. Despite months of planning, the Fuhrer’s ultimate goal remained to end the war on victorious terms, and the day after the discussion with Raeder, the Reich’s government signed the tripartite pact with Japan and Italy. This pact announced to the world the intention of the revisionist powers to prevent the expansion of the war and invited other countries to accept the New World Order .

Hitler’s next move was consistent with this path: he would extend Stalin an invitation to eliminate the reasons for a probable war between both countries and the visit of Molotov to Berlin on November 12 and 13 would be the time to do it.

The discussions between Molotov and Hitler went disastrously wrong. Molotov essentially rejected Hitler’s proposals and instead insisted on an agreement that not only meant Germany losing face in front of its allies but more importantly, permitted the USSR to expand towards the Balkans and Finland while threatening the most crucial raw material sources the Germans had. His demands (rather than proposals) were threatening the Germans as Hitler unequivocally pointed out during the talks . The conference ended in a tense atmosphere. The only hope of averting a complete break up between the allies was the Soviet foreign minister’s promise to present Hitler’s proposals to Stalin with the expectation that the latter would reconsider the whole situation and respond more constructively.

The day after Molotov’s departure, Raeder went to see Hitler once again and unsurprisingly, found the dictator quite pessimistic . However, Raeder had a good strategic mind and wanted to avert serious risks for Germany. Once more, he warned Hitler not to attempt the invasion of Russia until the successful defeat of Great Britain using substantive arguments. First, he indicated that Great Britain was gaining strength with the aid of the United States, but Germany was already strong enough to defeat the British if Berlin focused all its resources towards that objective.

Specifically, the production of submarines and aircraft should have priority to support army and navy operations in the Atlantic, Mediterranean, and Middle East and for strangling British imports. Second, the war against the USSR would entail a great expenditure of German strength. Third, it was not possible to say with any certainty how long this war would last, and finally, there was no impending risk of a Soviet attack on Germany because the Soviet Union needed German technology to modernize its navy and she would not attack in 2 or 3 years.

His advice did not sway Hitler much because the dictator had just learned of Stalin’s ambitions through Molotov and knew that the Red Army and air force had deployed in force at the common border. Therefore, the Fuhrer had to contend with the possibility that the USSR might try to seize the vital raw material centers in Sweden and Romania or that the USSR would declare war on Germany in the not-too-distant future when the conditions were least favorable to Berlin.

Within days of the discussion with Raeder, General Georg Thomas, who led the Military Economy Division in the OKW, presented Hitler a study requested by Field Marshall Hermann Goering. The latter’s position was that Germany should not invade the USSR before defeating England and he felt obliged to present convincing arguments to the Fuhrer to counter the Army’s optimistic posture.

Thomas’s approach was to present two what-if scenarios that contemplated the effect on the German economy in the case of a short-war and long-war with the USSR.

In 1940, the British blockade over Germany was ineffective. This happy state-of-affairs was the result of two factors: The control of large hubs of strategic raw materials acquired by direct conquest or accessible through importation from minor allies giving Germany considerable capacity to feed its military-industrial complex. Even this large pool of resources, however, was insufficient for several key strategic supplies that were unavailable in occupied Europe, but, and this was the other factor, Berlin imported the balance from the Soviet Union.

The Soviets delivered several important goods, like grain and oil, from their stocks and imported others from outside of the Soviet Union for the latter re-exporting to Germany (rubber for instance).

The study showed that Germany would suffer in case of war under both scenarios. In the case of a short war, exports of grains, oil, and other key raw materials would stop immediately, so unless the Germans captured large stocks of these supplies, seized intact the Caucasus oil fields, and somehow found how to transport the stores to Germany (a grave difficulty, since German commanders expected that the Soviets would destroy the rolling stock), the Third Reich would be worse off. Safety stocks would cushion the impact, but they would last only a few months if not replenished.

In the case of a long war, the after-effects would be awfully serious. Germany’s failure in reestablishing the Ukrainian agricultural supply chain meant its permanent loss with the consequence of famine in Russia and a deficit of foodstuffs for the Germans and Europeans. To prevent this distressing scenario, it would be necessary to replace the destroyed agricultural machinery, to substitute lost railroad rolling stock to transport the food surpluses to Germany, and to find fertilizers for the fields and foodstuff for the animal farms. All that effort would be in vain if simultaneously the Germans did not earmark POL (petroleum, oil, and lubricants) for farming production and its related transportation and finally, it would be necessary for farmers to stay to work the fields.

Without Russian oil Germany was barely able to obtain fuels for self-sufficiency, so allotting some of its fuel for agriculture production in the conquered Russian lands was a net drain of petroleum products that would only get worse the longer the war lasted.

Likewise, 75% of Soviet military-industrial potential and 100% of precision tools and optical industries were in western Russia , but to use this industrial capacity Germany had to seize the enemy factories in undamaged condition and rebuild the industrial supply chain: they had to capture undamaged power plants and furnish them with fuel for power generation. To complicate matters, many manufacturing plants depended on raw materials sourced from Asiatic Russia and thus it would not be possible to find substitutes for them.

In general, oil became the most critical bottleneck because Germany did not have extra capacity and Thomas established the absolute necessity to capture the Caucasus oil fields in working conditions as the only alternative. Hitler would later extend the objective line from Rostov-Gorki-Archangelsk as originally established by Marcks to the Volga River-Archangelsk to include the Caucasus.

Furthermore, even doing the above, Germany would be short of jute, asbestos, zinc, platinum, copper, rubber, and tungsten until the establishment of a link with the Far East was in place.

The probability that Germany could meet all of Thomas’ requirements simultaneously was low and thus the risks of attacking the Soviet Union were glaringly obvious. This was a sobering report.

Overall, to the military-strategic warnings of Raeder and Goering relative to the risk of embarking in a two-front war, Thomas added economic considerations that underscored the grave risks of this course of action.

Hitler faced a dilemma. He wanted to reach an agreement with Stalin to prevent these colossal risks. He wanted to limit the scope of the war and focus his efforts on defeating Great Britain , but he had to consider the possibilities of a Soviet attack (he was, after all, concerned with the massive Soviet military force deployed at the border, including the frenetic construction of dozens of airfields close to the frontier which were filled with attack aircraft ). He also faced the danger of the Soviet Union switching sides (which was Great Britain’s main diplomatic goal).

On 26 November 1940, a bombshell landed on Hitler’s desk: The expected response of Stalin to his proposals was negative which translated into an impossible-to-ignore risk of war .

Stalin’s unfriendly response coupled with Brauchitsch reassurances of 5 December 1940, that promised a swift German victory in case of war with Russia, almost surely convinced Hitler to attack (see figure below). The German government never responded to the Soviet government’s counterproposal.

The decision to attack was not an illogical posture because if Moscow switched sides or attacked Germany, the risks that Raeder, Goering, and Thomas had underlined, would materialize regardless.

Hitler’s situation at the end of 1940 was not unlike the one he faced in 1939. Back then, Stalin was a threat: He was negotiating a possible alliance with German enemies. And the Red Army was more dangerous then because it was large, its performance unknown and more importantly, Germany had to cope with the Polish, French, and British armies simultaneously, making the Red Army relatively more powerful vis-à-vis the Wehrmacht because only a fraction of the German army was available to counter the Soviets. In 1939, Hitler took the rational course of reaching an agreement with Stalin in terms much more favorable to the Georgian than to Germany.

In December 1940, the Fuehrer faced a similar scenario again. Stalin knew the might of the Soviet army. His staff could also play war games and with the expected ratio of forces, he likely resolved that any war with Germany would be long . Consequently, in his eyes, Germany faced the mighty risk of engaging in a two-front war. This led him to the logical conclusion that he had a very strong hand and the Fuehrer would have to negotiate on his terms as in 1939 (see previous figure: Relatively-strong-Red-Army-and-USSR-a-clear-and-present-danger setting). Molotov’s position during the negotiation and Stalin’s subsequent rejection of German terms are consistent with this scenario.

Hitler’s decision to attack was also logical based on the assumptions that the German army was much stronger than its adversary and that the Soviet Union presented a clear and present danger.

A logical decision, however, does not mean a correct decision. If the assumptions are incorrect, a logical argument will be incorrect.

With hindsight, we can appreciate that the failure of the Hitler-Molotov negotiation on 12-13 November 1940 and Stalin’s government subsequent letter of rejection on 26 November set the stage for the grimmest conflict humanity had ever seen. It ironically hastened the auto-destruction of the two systems that challenged capitalism in the 20th Century . This was apparently, the last direct communication at the highest level between both governments.

The miscalculation of both dictators would terribly affect the lives of 170 million Soviets and 76 million Germans and would send to their deaths more than 26 million of the former and over 7 million of the latter . The conflict would also destroy the lives of an enormous number of other foreigners.

Geopolitically, both dictators enabled the triumph of the capitalist United States at a very low cost to this country.

Had they decided to reach an agreement in that fateful month, the course of history would have been completely different.

Even though Hitler’s decision is understandable, it was arguably his worst decision during the whole war. First, he failed to detect the monumental failure of his Intelligence community in assessing the Red Army strength (the record does not show any effort on his part to question this critical piece of information) and he also proved unable to grasp the consequences that the underestimation of the enemy could entail.

Second, after he chose to invade, the Fuehrer implemented his decision in a most defective manner.

War should only be waged if it can be won. The risks of a protracted armed conflict with Moscow were so evident (as Hitler recognized thanks to the arguments put forth by the Kriegsmarine and the Luftwaffe ) that the German leader should have left no stone unturned to minimize them.

It is at this point that the inadequate grand strategic outlook of the dictator becomes evident for the first time.

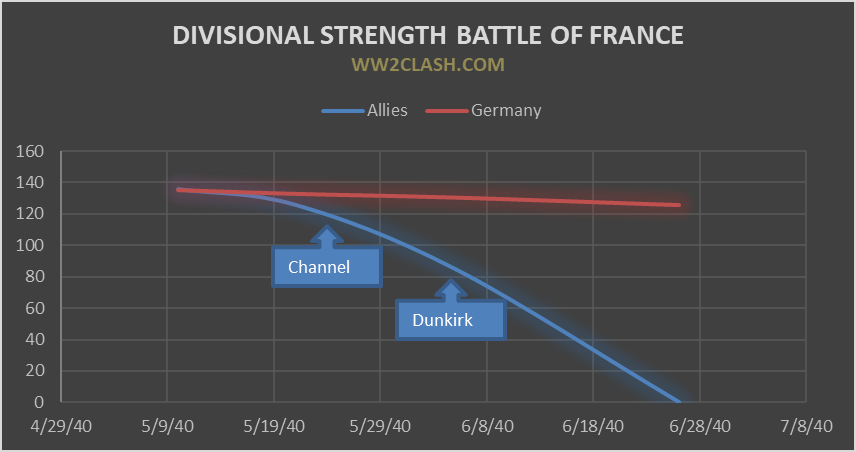

The basic concept for overcoming another army in combat is called “defeat in detail”. Instead of attempting to defeat all the enemy army in one fell swoop, one portion of it is engaged and destroyed. Ideally, the attacker achieves a sizeable numerical superiority, which facilitates crushing the next segment of the enemy army and so on until total victory is achieved.

The Germans subjugated France using this concept. They encircled a significant slice of the rival army by reaching the channel coast and then eliminated the troops trapped in the Dunkirk pocket.

As can be seen in the next figure, both armies started the battle with almost the same number of divisions. When the Wehrmacht reached the channel, the antagonist armies remained broadly comparable: only the Dutch army had been defeated giving the Germans slight superiority.

The elimination of the Dunkirk cauldron handed the Germans the decisive numerical superiority they needed to overrun the rest of France. The escape of British and French troops by sea was inconsequential to the German victory since they lost all their equipment and were effectively nullified.

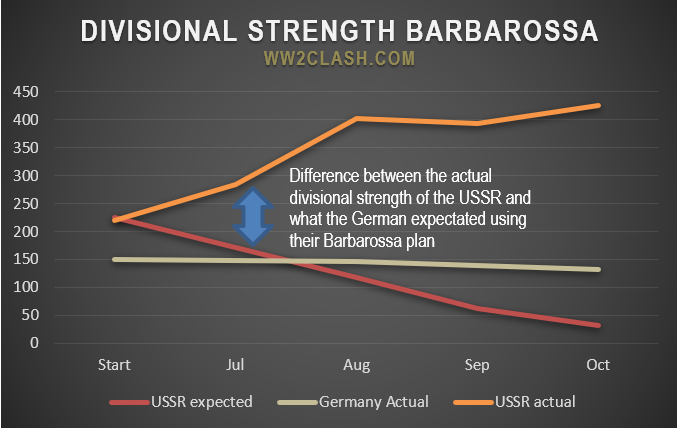

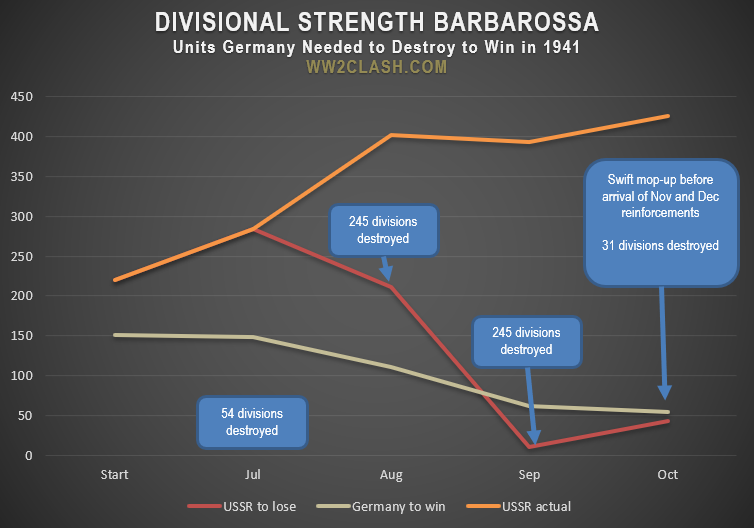

Barbarossa’s concept was similar (see the next figure). The Germans knew they would start from a position of numerical inferiority (compare the gray and red lines), but by encircling and destroying the Soviet Western Front they expected to achieve a telling numerical superiority by August and attain complete dominance during September when the wings had been cleared. After that, the last reserves would be mopped up.

The Wehrmacht accomplished the levels of destruction that it projected, destroying a Soviet force equivalent to between 229 and 256 divisions by 31 December 1941. This should have given the Germans their expected victory since we know the Soviets deployed 220 divisions on 22 June 1941.

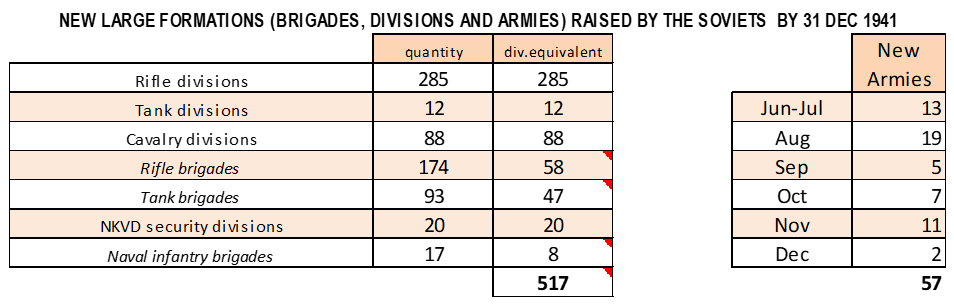

However, Stalin had built a large reserve and could mobilize it rapidly. From 22 June to 31 December 1941, 57 new armies appeared in the Red Army Order of Battle, and 517 new divisions were fielded.

Despite the destruction of a force equivalent to the whole Red Army deployed on 22 June 1941, the Soviet reserves ensured that the RKKA not only kept its numerical superiority but increased it throughout the year.

Contrary to what the German generals claimed, this numerical imbalance could not be redressed by simply storming towards Moscow leaving the flanks vulnerable. The original (OKW) plan achieved the destruction of at least 229 divisions. To win, the early attack on Moscow should have destroyed 245 enemy divisions in August and the same amount in September to have some days for final mop-up in October before new Red Army reinforcements arrived (see next image).

In other words, the Wehrmacht should have destroyed in one month, the same number of divisions it destroyed during the 6 months of 1941…and then it would have to repeat the same feat the following month!.

It ought to be evident that not even the Blitzkrieg could achieve such a result. The Germans should have planned for a long attrition war.

It must be said that even this implausible scenario had a narrow margin of success for two reasons. First, the cost of the Blitzkrieg was not cheap. For every 5 divisions destroyed the German army was losing one of its own. The obliteration of so many Soviet units implied that the German army would have been close to destroying itself in the process. Second, the German army should have kept just enough force to defeat the Red Army’s October reinforcements before the rainy season arrived and convince Stalin to surrender. Otherwise, the November and December reinforcements could have prolonged the war due to the weakness of the German army at that point.