For the Germans, only the offensive brings victory. The goal of defense was to halt an enemy attack until the conditions were ripe to resume the offensive or to gain time for offensives in other sectors to bring victory.

An effective defense line must halt the enemy’s attack in front of the main line of resistance (MLR) and force the enemy to abandon his assault. An efficient defense line accomplishes this objective using the smallest number of troops and weapons to protect the largest possible sector.

To defeat an attack the Germans developed a doctrine that combined rigid and flexible elements. Within a Corps or Army sector, infantry divisions held the line (rigid element) and a mobile division (flexible element) remained as tactical reserve at no more than 1 day’s march to carry out aggressive counterattacks to stop the enemy penetration if the infantry divisions failed to prevent a breach. Even in the latter case, the infantry divisions continued defending tenaciously holding their ground to prevent the widening of the breach and thus facilitating the mobile division attack. Armored divisions kept as operational reserve at Army or Army group level further back (3-day’s march usually), executed violent counterstrokes to send the enemy troops reeling back to their original positions and to force them to abandon the offensive and defend, surrendering the initiative. The forward elements had to resist at least 3 days until help arrived.

The German Infantry Divisions held the first line of defense because the foot soldier remains the backbone of any resistance and they had more infantry battalions than a panzer division, whose mobility and firepower made them better suited for attack.

The Wehrmacht designed German divisions to forcefully defend sectors of up to 10 km wide. The large distances found in the Eastern Front and shortage of troops, usually forced the Germans to shield wider sectors, but at the risk of presenting a more porous defense. The width of the sectors assigned to German groupings depended mainly on their size and secondarily on the terrain they defended. If the terrain was difficult for the attackers, the defenders could guard a sector as large as that shown in the Maximum Sector Width of the next table, whereas easy terrain required higher density and thence shorter sectors:

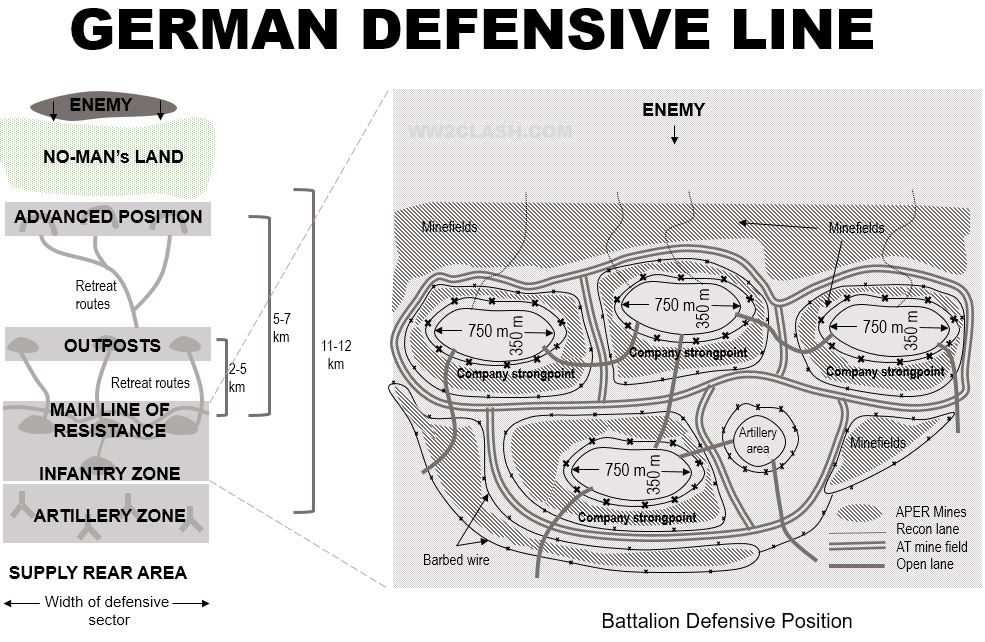

The German defense line was not simply a long trench filled with soldiers, it was much more sophisticated than that. There were 3 consecutive sectors:

Advanced Position. Established 5 to 7 kilometers in front of the main line of resistance occupying important terrain features such as river crossings, crossroads, or other commanding ground. Reconnaissance detachments with mobility and firepower manned this position to force the enemy to deploy prematurely.

This advance position was within the range of the divisional medium artillery (which had a range of 11.5 to 12.5 km) and did not defend the position at all costs. If enemy pressure was considerable, the forces retired through preselected routes under the protection of friendly artillery fire. This position only existed when the front lines were fluid.

Outpost Position situated 2 to 5 kilometers in front of the main line of resistance at the edge of woods, villages, hedgerows, and hills It consisted of machine gun nests and fusiliers, supported by mortars, infantry guns and anti-tank guns drawn from the main battle line. Each weapon had several alternative locations for rapid shifting and for preventing rapid detection. The Germans also scattered dummy positions to confuse the enemy.

These positions commanded carefully selected fields of fire. The defenders planed small attacks to keep the enemy off-balance and in case of a superior enemy force, they evacuated the outposts through established routes under covering fire from their light or medium artillery. The Germans also registered carefully these positions to deliver withering artillery fire in the evacuated positions and thus prevent its occupation by the enemy.

The Main Line of Resistance (MLR), behind the outposts, constitutes the hardcore of the defense. This position contained individual strongpoints arranged in depth and interconnected to form an uninterrupted defensive belt while artillery guns occupied positions behind it.

The thinly defended supply area spreads beyond the artillery zone. Each strongpoint could defend from all directions. Antipersonnel and antitank mine fields surrounded the whole position, protecting it. Barbed wire deployed all-around minimized infiltration. The soldiers connected adjacent strongpoints through narrow tracks free of mines and barbed wire to allow resupply and to improve mutual protection (for instance, allowing counterattacks on a neighboring strongpoint). They also opened lanes through the minefields to allow reconnaissance and to permit positioning of listening post. Supporting light artillery was placed at specific points to stiffen the defenders.

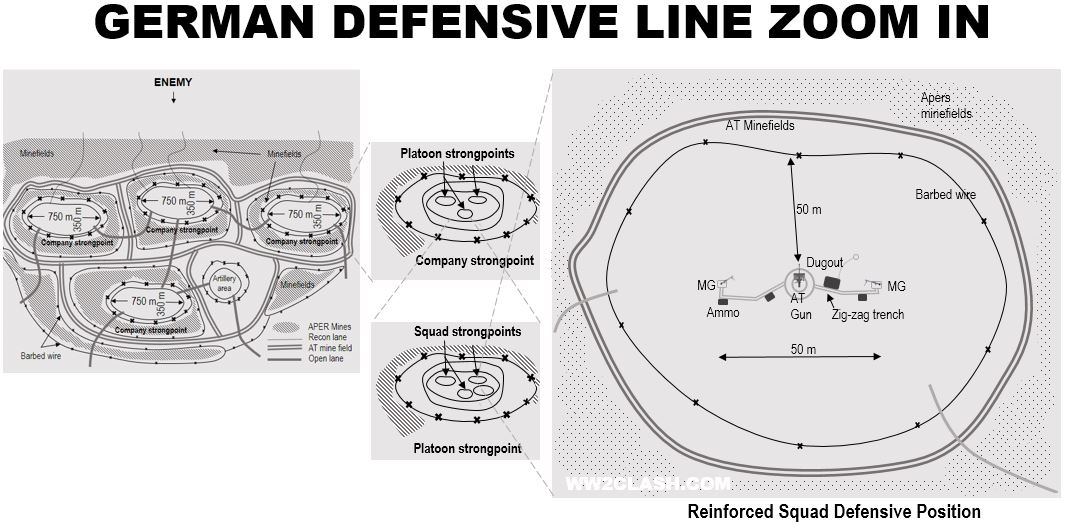

The strongpoints themselves resemble Russian Matryoshka dolls, that is, they are nested: thus, battalion strongpoints consisted of company strongpoints which themselves contained platoon ones, which incorporated several squad defensive positions.

The smallest strongpoint typically consisted of a reinforced squad occupying a zig-zag trench of 40 to 60 meters long (130-200 ft) kept firm with wooden logs on the trench walls. 2 machine gun nests at opposite sides provided flanking fire. An emplacement for an antitank gun or 81mm mortar, usually at the center afforded supporting firepower. 4 dugouts constructed with 3 layers of logs and earth protect soldiers from artillery barrages and permitted the storage of ammo, food, and supplies. It also gave protection against weather. Since these positions did not have sewage or trash collecting services and they were occupied for days, weeks or even months, one can imagine how filth rapidly developed.

Even if the enemy encircled one position, German troops continued the defense to facilitate counterattacks and to hinder the opponent’s advance. Tenaciously defended pockets frustrated enemy supply, reduced advance to a crawl, and thus helped to stop the assault.

If the enemy achieved a wide enough penetration and it was not possible to dislodge the attack, the defense commander faced two options. He might order a general counterattack using available reserves or the abandonment of the position to establish a new defensive line farther to the rear. In the first case, his staff used a thoroughly pre-planned counterattack directed against the flanks of the penetration or, if the situation was critical, a frontal attack to seal off the area.

THE RETREAT

Because the retreat is a very difficult maneuver to execute, the Germans planned it carefully. The first thing they did is to reconnoiter and mark the withdrawal routes. They then initiated the rearward movement of supplies, equipment, and vehicles, using covering forces that maintained a strong fire with all available weapons to deceive the enemy into believing that no retreat was underway.

Engineers prepared additional minefields and booby traps to make the pursuit by the enemy difficult.

The main body started to withdraw, keeping in place a strong rear guard to carry out a delaying action. The covering forces remained in contact with the enemy until it started to advance, or if it failed to do so, after a specified time-interval.

The purpose of delaying actions was to allow an orderly retreat of the main body and the establishment of a new defensive position that could be defended properly. The rear-guard fought delaying actions from successive lines of resistance that were not previously prepared and that did not have much depth. Units fighting delaying actions covered sectors twice as long as those fighting a defensive action