In August 1936 Moscow became involved in the Spanish Civil war to further the cause of the Republicans and by October the Soviets were sending weaponry and military personnel to the peninsula. Stalin sent the most advanced military equipment at his disposal and Soviet troops would soon face the German Condor Legion which supported the Nationalists. It was the beginning of a proxy war fought between the two adversaries and Stalin stepped up his measures for a future confrontation with Germany . His second five-year plan (1933-1937) was already in full swing for the benefit of the RKKA which was already the largest military force in Europe. The Spanish war would allow the Soviets to test weapons and fine-tune tactics.

All armies have high command staffs whose function is to prepare plans for every eventuality and the Red Army devised defensive and offensive war plans that were updated periodically. Hostilities in Europe between capitalist states appeared very probable as early as 1935 and the Russians prepared methodically for this contingency.

By 1941 a highly developed defensive plan termed DP-41 was in existence. One key feature of this blueprint is that the Soviet Supreme Command designed it to defeat an invasion in two fronts simultaneously: against Germany from the west and against Japan from the east. The Soviet High Command anticipated an attacking force consisting of 270 divisions: 233 in the main European front and 37 in the Far East. They assumed that the Germans would launch the invasion with the support of Italian, Finnish, Romanian, and Hungarian forces while the Japanese attacked from Asia. Given the size of the adversaries’ military forces and the location of the Soviet Union industrial areas, they recognized that the most important threat came from the west . The noteworthy quality of DP-41 is that the Red Army Staff planned against a worst-case scenario, eschewing any wishful thinking.

The Russians established that to defeat the Western invasion, a force of at least 171 divisions in 3 defensive belts (57 in the first belt, 52 in the second belt and 62 in the third) was necessary. Thus, they expected an enemy’s numerical superiority of 233-to-171 or 36%, but Soviet Generals understood that defense has an advantage over the offense and hence, they judged such force sufficient to defeat an invader.

Based on the experience of the Great War, the Russians assumed grievous fatalities, anticipating the loss of their entire deployed forces every 4 to 8 months of fighting and the need to replace them. To restore the strength of these depleted formations with such an appalling casualty rate, they proceeded to amass large weapon stocks, to instruct sufficient reserves and to gear up their military-industrial complex and military school training system. This they did, through a process that took 10 years to complete, giving DP-41 a very robust foundation. This is compelling evidence of two qualities of Stalin’s communist government: the ability to think with clarity in the longer term and aptitude to execute wide-ranging plans that demand a national effort.

By analyzing the geography of the threatened western districts, the Soviets realized that the Pripet Marshes divided the front in a northern and southern sector preventing a connected defense. The Pripet Marshes is a large region of wetlands, approximately 480 km (300 miles) east-to-west and 225 km (140 miles) north-to-south situated in southern Belarus and northwest Ukraine (see following map). The area is, for practical purposes, impassable for large military forces.

It is heavily wooded, and it has few roads, but these are not the main factors that preclude large-scale mobility. Rather, it is the large swamps, ponds, and rivers interspersed through this region that make the movement of heavy vehicles exceedingly difficult. Even under favorable conditions, crossing this area on foot or horse is problematic due to soggy ground. Melting snow and rainfall cause extensive flooding that convert the terrain into a near-impenetrable ground. Words sometimes are insufficient to convey the difficulty this region prompted on the movement of vehicles because the average reader usually drives through well-paved roads or at most, dry dirt trails. But off-road enthusiasts are aware of how even well-equipped 4x4 vehicles cannot traverse through many areas. The next picture does an excellent job of showing the hard going this terrain entails.

This great obstacle separates an assaulting army in two and the invader, therefore, must decide if his main effort should fell north or south of the marshes. After prolonged discussions, the Russians decided that the Germans would select their main effort in the south.

They envisaged a direct advance on Kiev from Krakow with a converging secondary prong from Romania (see map). The estimated magnitude of this southern offensive stood at 14 panzer divisions supported with 135 to 160 infantry divisions. To give some perspective, this projected southern force was larger than all the forces utilized by the Germans to invade France in 1940. Also, in the northern sector, they expected another 60 to 90 infantry divisions stiffened with 1 or 2 Panzer divisions to launch a secondary two-prong attack: From Konigsberg to the Baltic States and from Warsaw to Minsk and Smolensk .

The proper determination of the enemy’s main point-of-effort is so critical, that there was much debate. Alexander Vasilevskiy, Deputy Chief of Staff at the time, predicted the main thrust north of the Pripet Marshes .

However, ultimately, the plan supported the southern hypothesis, based on the views of Stalin and Georgi Zhukov. There were good reasons for that. The clear terrain in the south was very favorable for tank operations and did not offer concealment to the defender, in contrast to the wooded terrain in the north . Moreover, the indispensable oil fields in the Caucasus were in the south, as well as other key strategic sources of food and raw materials throughout Ukraine.

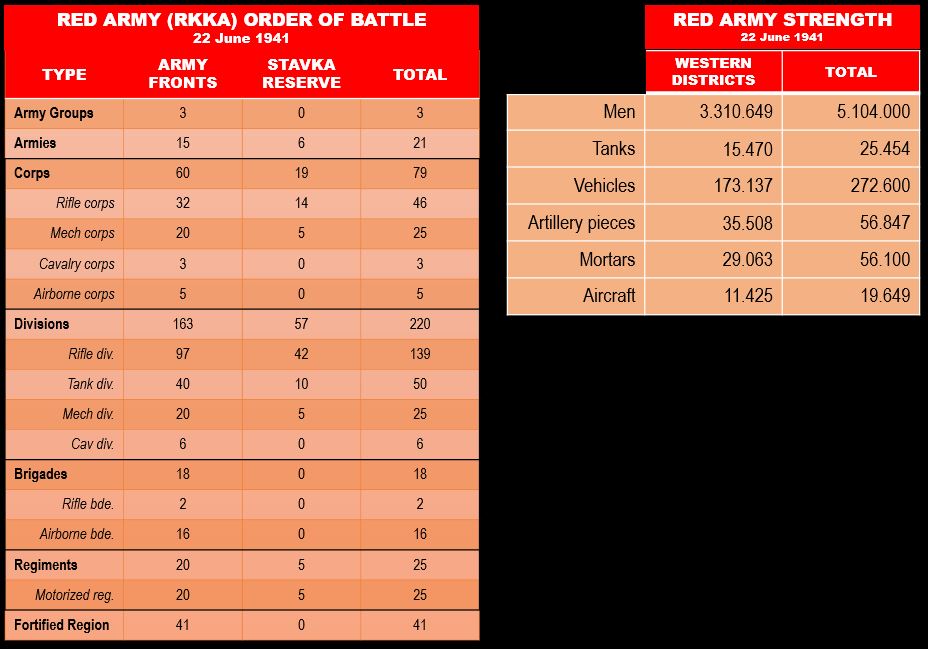

To defend against this threat the Red Army deployed 220 divisions west of Moscow on the eve of the German offensive: 163 of them in three successive defensive belts starting at the border and a further 57 divisions in operational reserve further back (see next map). This force exceeded substantially the 171 divisions deemed to be the absolute minimum to defeat the German onslaught according to DP-41. The strength of the arrayed defensive force surpassed the established minimum by more than 29%, giving the Soviet High Command reasons for confidence.

The Order of Battle that the Russians disposed to oppose an invasion from the west was certainly formidable:

Three Army Groups (called Fronts), 21 armies, 79 corps, and 220 divisions. 75 of these divisions, a third of the total, were tank or motorized infantry divisions, 139 were rifle divisions and 6 were cavalry, all deployed in the western districts and as Stavka reserve. Notably, there were also 16 parachute brigades comprising 5 airborne corps. This force structure amounted to 3.310.649 men, 15.470 tanks, 35.508 artillery pieces (including AA guns) and 11.425 aircraft .

The whole Red Army, totaling the formations in the Far East and the rest of the country, numbered 5.104.000 soldiers in the ground army and air force (476.000 of them in the VVS) organized in 304 divisions, with 25.454 tanks, 19.649 combat aircraft, 48.247 artillery pieces (calibers between 45-305mm), 8.600 AA guns (between 25-85mm), 56.100 mortars (between 50-120mm), and 272.600 motor vehicles of all types . The Far East forces alone, defending against a possible Japanese attack, consisted of 4 armies, 23 divisions, 500.000 men, 3.200 tanks and 4.100 combat aircraft, under General Eremenko.

This huge army was the largest and best-equipped force in the world. The VVS was numerically the strongest air force in the globe by a wide margin. The only category where the Red Army was numerically inferior to the Wehrmacht is in the number of motorized vehicles, less than half. An indicator that reflects a lack of mobility of the Red Army. The size of the land army, including reserves, was unsurpassed by any other power throughout the entire war .

Furthermore, the army gained experience in Spain and had the opportunity to prove itself in battle recently. The Russians invaded Poland in 1939, testing the operational mobility of the RKKA, and fought wars against Japan and Finland. The Red Army’s performance exposed its serious deficiencies on the attack, but it demonstrated toughness and resilience on the defense. Neither Japan nor Finland proved capable of piercing the Soviet lines at operational depth and the red air force gained local air superiority in both cases. Feebly against the Finns and convincingly against the Japanese.

This strong defense allowed to tip the scales in the Red Army’s favor when it eventually brought to bear its numerical superiority to swamp the adversaries. Just like the Wehrmacht did after the invasion of Poland and France, the RKKA studied its operative mistakes and took corrective action. Similarly, it studied German successes, adopted some of their principles and prepared countermeasures.

If the Germans did attack, the Russians remained confident they would stop the invaders west of the Dnieper river based on the ratio of forces. They also started rearming before Germany and enjoyed more time to train, equip and organize their army.

A deeper Nazi penetration appeared difficult to achieve due to the limited size of the road and rail network and the railroad track width, unsuitable for German rolling stock. Since contemporary armies depended on the rail networks for supply and in all the Soviet Union only 82.000 km (51.000 miles) of track was available, the more the invaders advanced the greater the difficulties to keep their armies supplied.

This lofty confidence continued even on the day the Germans finally attacked: The Soviet High Command ordered their troops to destroy the invaders but not to cross the frontier !

The actual RKKA’s deployment in Western Europe had defensive and offensive characteristics. Each of the armies protecting the border placed their rifle divisions close to the frontier; every division securing 35 km (22 miles) sectors on average. Commanders took maximum advantage of rivers, placing the rifle divisions behind them, thus reducing the surprise and mobility potential of the German army.

A World War II division could fend off attacks while defending a 10km sector or it could fight a delaying action (exchanging space for time) screening a 20km sector, hence, by selecting to thinly defend the border it was not possible to prevent the German army from finding meagerly protected areas to penetrate them, even considering that numerous fortified regions bolstered defense lines in all districts .

However, each Soviet army deployed at least one mechanized corps and sometimes two, behind the rifle corps as a tactical reserve to launch vigorous counterattacks that had the objective of stopping the German advance.

Behind the mechanized corps assigned to every army defending the frontier, the Border Military Districts positioned a third echelon (up to 400 km, 250miles, from the border) as their operational reserves to launch heavy counterstrokes forcing the Germans on the defense or to allow the creation of new defensive lines in the rear if things were not turning out as planned.

Finally, Stavka prepared a fourth echelon with strategic reserves behind the operational reserves to hurl them at the appropriate moment and force the Germans to retreat. The Soviet mechanized corps had enough tanks to unambiguously outnumber the opposing Panzergruppen in quantity and quality .

Even though the mechanized corps in the third and fourth echelons deployed fewer tanks than those in the second echelon, they still outnumbered by themselves the total number of German tanks .

The Soviet high command recognized the importance of achieving air superiority over the battlefield and supported each military district with one air army, every one composed of 5 to 10 air divisions. These powerful air formations fielded 6.510 aircraft making them numerically as strong as or stronger than the Luftflotten each one faced. To this number, we need to add the 1.179 fighters of the PVO (Home Defense), 1.333 bombers of the DBA (Long-Range Bomber Aviation), 380 of the corps tactical observation force, 656 of the Leningrad Naval Aviation, 624 of the Odessa Naval Aviation, 150 aircraft belonging to the NKVD, and 593 transports mobilized from the Civil Aviation (the GVF) three days after the invasion for an impressive total of 11.425 aircraft. Another 8.224 aircraft remained as a reserve in the interior districts and the Far East.

Lastly, a vast pool of 14 million trained reservists remained available, unassigned to combat units but prepared to form new formations.

In the Southwestern front, where the Stavka expected the Wehrmacht maximum effort, the defenders arrayed in even greater depth and with greater troop density; each division covering 24 km (15 miles) sectors . The 5th and 6th armies, defending the most vulnerable areas positioned their corps in 2 echelons of great depth, while powerful district reserves stood behind buttressing these defensive belts. Moreover, 3 armies (16th, 19th, and 21st) from the strategic reserve waited close to the Dnieper River.

Overall on 22 June 1941, only around 25% of the available red divisions shielded the border on the first echelon. The rest, three-quarters of the force, provided depth and resilience to the defense, a countermeasure devised to thwart the blitzkrieg. By the time the Germans attacked the first belt, the successive Soviet echelons would enjoy ample forewarning.

The red army disposition, remarkably, exhibited several clear offensive features:

• Significant forces remained well forward in all sectors, threatening German territories. The 8th and 11th armies occupied positions a few miles from Prussian towns like Memel and Gumbinnen. The powerful 10th army, poised nearest to Berlin was particularly menacing (from the border to Berlin is the same distance than from the frontier to Smolensk). However, this location, semi-surrounded by enemy territory was vulnerable to attack. The campaign in Poland showed the risk of facilitating German encirclements by faulty forward deployment and the Soviets, after analyzing that campaign, probably recognized it but chose to do it regardless, for some reason.

• The strongest and best trained mechanized corps were close to the border, in the second echelon: 3rd MC (Baltic District), 6th MC, (Western District), and 4th MC (Kiev District). This allowed the launching of offensives towards enemy vulnerable sectors (East Prussia, Poznan, and Krakow).

• The Baltic, Western and Kiev Military districts controlled one airborne corps each. Paratroops exist as offensive troops meant to attack behind enemy lines to support mechanized offensive drives. If the Red Army was not contemplating an offensive, their place was in the rear, as Stavka reserve, not forward.

• Another crack mechanized corps (the 2nd MC) supported by one airborne corps was in Romania threatening the Romanian oilfields.

• The Russians constructed, with significant effort, an impressive number of airfields near the border and then filled them to the brim with combat aircraft . These locations make sense if the RKKA was preparing an offensive and needed to penetrate hostile airspace, otherwise, they become highly vulnerable to attack. For defense, airbases farther from the front are sensible because they can still protect their ground armies and they enjoy more time to respond to the hazard of incoming attacking aircraft. The previous year, the British found that their landing strips near the coast, at a 15-minute flying time from standard detection range (70 km or 45 miles) presented an easy target and they situated their main fighter bases at twice that distance. Also, the RAF based no more than 2 squadrons (about 40 aircraft) per airfield to prevent vulnerabilities caused by excessive air density. British forward air bases did not host permanent squadrons.

• The Red Navy occupied bases on the Baltic coast capable of interdicting German iron ore imports from Sweden.

The characteristics of this deployment strongly suggest deliberate readiness on the part of the RKKA for a large-scale attack.

This does not necessarily imply that the Red Army was about to launch an assault in the summer of 1941 , but not even the stupidest German politician could afford to ignore the grave danger to Germany.

When the Wehrmacht began relocating significant troops to Poland, Moscow was quick to request Berlin an explanation, as this was a threatening sign . It should have been quite obvious to Stalin that his deployment was causing alarm to the Germans .

If Stalin and his generals had known with accuracy the German Order of Battle arranged against them, their confidence would probably have increased. The actual forces that the Germans and its allies marshaled for the invasion were significantly smaller than the projections in DP-41. Germany and her allies committed 183 divisions instead of 233, almost a quarter less than planned, and less than 4.000 tanks when they estimated 10.000 (only 40%) .

Stalin would have been even more self-assured had he known the number of German replacements. Only 321.000 troops were available as compared with the 14 million that the Soviets trained. An overwhelming 40-to-1 Russian advantage.

In terms of weaponry, the Germans deployed 3.801 tanks and 3.415 aircraft of all types. The numerical superiority of the Russian armament appears overpowering: 4-to-1 in tanks and 3-to-1 in aircraft excluding the Soviet units in non-western districts . While the Germans employed 32 armored and motorized divisions, the Soviets had 75 immediately available. In summary, the Soviets were 29% stronger and the enemy was 21% weaker as compared with DP-41. They also enjoyed a significant numerical superiority in equipment and had a fabulous capability to restore depleted units.

In theory, Russia had nothing to fear.

With the benefit of hindsight, a rational observer that reflects on the major objective variables that have a bearing on war’s outcome, cannot fail to see that the Soviet Union, thanks to its superiority on army size, raw materials availability, size of the country and population, mobilization potential (for munitions production and reserves training), and systematic preparation, was capable of preventing a rapid defeat and eventually to turn the tide in its favor.

In a long-drawn-out conflict between large enemies with asymmetric war potential, the USSR had a telling advantage. History shows that the victor is almost always the side that enjoys a substantial material preponderance as long as it can keep itself technologically competitive. Local, temporary victories by the smaller side are possible, but they just delay the inevitable . Stalin, so far, had played his hand admirably.

However, factually, the Russians stumbled badly and were very close to defeat during the first year of the war. Subjective variables also played a most important part in the conflict and it is here where the Soviet leaders, Stalin, and his commanders, made serious mistakes.

The Germans benefited greatly from four major mistaken Soviet assumptions:

First, the actual point of main effort of the German offensive was North of the Pripet Marshes, not South as the Russian High Command expected. So, the Red Army deployed incorrectly. Although numerically the RKKA’s tank strength exceeded considerably the Wehrmacht’s, this was not the case in the German’s point of main effort. The Special Western Military District totaled only 2.316 tanks against 2.230 of Army Group Center, a near-numerical parity . Worse, the German concentrated the bulk of their best tanks in this sector (700 class A, 507 class B, 809 class C, and 214 other types ).

The Western Front tank distribution of 1.149 Class A’s T-26, 520 Class B’s BT-tanks, 385 Class C’s T-34 and KV (plus 262 other minor types scattered in the three categories) gave it a significant numerical disadvantage in the all-important medium/heavy tank category .

More importantly, despite a marked numerical superiority of the VVS over the whole theater of operations, the opposing air forces in the central sector fought with a near numerical parity, and to make matters worse for the defenders, Luftflotte 2 enjoyed a distinct qualitative edge over the Soviets. 1.470 German aircraft, including all the Stuka dive-bombers, faced 1.532 Soviet airplanes which lacked accurate bombers and enough reconnaissance planes. Kesselring’s air force also had at its disposal the most powerful anti-aircraft corps in the whole German Army, a type of formation that did not exist in the RKKA or VVS.

In comparison, Army Group South’s 1st Panzergruppe had 792 tanks to oppose the 4.663 of the Southwestern Front’s mechanized corps, that included 766 medium and heavy tanks (the majority of Class-C’s tanks available to the Red Army). Against the numerous T-34s and KVs, the Germans could only boast 455 Panzer III and IVs. To this large number of Soviet tanks, we must add another 809 in the mechanized corps of the Southern front (that also included another 60 T-34s and KVs).

Notably, Luftflotte 4 would confront an almost 1-to-3 numerical inferiority in the southern sector. No wonder the Germans faced a much tougher challenge here.

Second, Stalin’s belief that it was implausible that the German dictator would launch a two-front war, lured him to deploy his army in a quasi-offensive disposition making it vulnerable. So far, Adolf Hitler had displayed a bold but very rational behavior in the conduct of the war, and it seemed to Moscow that the Fuehrer would not dare to unleash such a gigantic gamble. Under such an assumption, the Soviet Union could benefit by maintaining pressure on Berlin and by continuing preparations to attack if Germany became sufficiently weakened in its conflict with Britain.

While the Red Army’s deployment in depth limited the effect of surprise considerably, the forward placement of the bulk of its air force disallowed proper defense of airfields and loss of air superiority followed, giving the Germans the strategic initiative.

Third, the Soviet High Command overvalued the capability of the Red Army. Stalin found, after the fact, that the army’s leadership, training, and methods were faulty. He specifically assumed that the effect of the purges of the late ‘30s was not very detrimental to the RKKA efficacy . He was wrong.

After the assassination of the popular Leningrad party boss Sergei Kirov in December 1934, a probable rival of Stalin, the dictator launched a nation-wide purge of the communist party to eliminate any potential opponent who could conceivably threaten his power. The suspicious dictator enlarged the purge to include the army when on 11 May 1937, he relegated Marshal Mikhail Tukhachevsky, Deputy Minister of Defense under Voroshilov and one of the brightest minds in the Red Army to command a minor military district in the Volga. Soon thereafter the NKVD arrested him, brutally tortured him, and shot him dead .

Stalin, unsatisfied with the torture and death of his general, ordered the arrest of Mikhail’s mother, brothers, sisters and his beautiful wife, Nina. Later, he ordered the execution of Nina and Tukhachevsky’s brothers. His mother and one of his sisters died in prison. Three other sisters survived without their husbands, shot also. Mikhail and Nina’s daughter, underage at the time of her detention, suffered arrest when she attained her age of majority .

This was just the beginning, Stalin sacked, imprisoned or liquidated 3 out of 5 Marshals of the Soviet Union, 11 of 13 army commanders, 57 of 85 corps commanders and 110 of 195 division commanders as well as thousands of junior officers . The Red Army was under tremendous expansion, and it needed to dismiss a significant percentage of officers that did not have the qualities to command men in modern war or which were a hindrance for several reasons. The same happened in other armies. For that reason, some voices insist that the purge in the Soviet Union did not affect markedly the Red Army efficacy.

These opinions are probably wrong. One thing is to remove underperformers and other is to execute some of the brightest minds for political reasons. In an environment of fear and self-preservation the theories of removed individuals lose weight, teamwork suffers, and initiative and confidence to implement necessary changes diminish dramatically.

By 1941, the Russian High Command had obtained some factual evidence that something was wrong with the army: during the 1939 invasion of Poland and the 1940 war against Finland, the Red Army enjoyed a tremendous material advantage but fought clumsily. The logistics to support the offensive suffered from bad coordination (i.e. in Poland, despite the relatively short distances involved, the Red Army was not able to advance with full units and had to pool fuel to allow part of its forces to move ahead). Responsible commanders applied corrective actions, but they proved insufficient, despite having more than a year for full implementation .

Undoubtedly, the purges helped Stalin to strengthen his power and discourage opposition. During the whole war, the Soviet officers did not attempt at any time to kill or remove Stalin from power and displayed remarkable loyalty. This continued to be the case even under the disastrous defeats of the first year and a half. However, the efficacy of the army suffered badly. The surviving commanders found it difficult to lead large formations and within weeks of the invasion, Stavka found necessary to carry out a full-scale restructuring to simplify the field-unit structures allowing less skilled commanders to carry out their jobs. This is a clear indicator of their lack of experience.

Hitler, on the other hand, carried out his mini purge in 1938, when he removed the Minister of Defense, Werner von Blomberg, and the Army Supreme Commander, Werner von Fritsch, along with other officers perceived as uncooperative. The dictator did not kill or imprison any of them, or their families. Curiously, most historians have fiercely criticized this ouster as an example of Hitler’s ruthlessness and excess , but in comparison with Stalin’s, the Fuehrer’s effort was exceedingly timid. The Chief of Staff, Ludwig Beck remained in his post as well as Admiral Canaris, both of whom remained conspirators and sought to undermine Hitler at every opportunity. While the performance of the German army continued unaffected, he was incapable of attaining the same level of loyalty as Stalin did. The plotters inside Germany eventually became emboldened and a large circle of the generals did their best to weaken the head of state. Even when Beck quit his post, he continued to challenge the regime and he remained in close contact with Halder, his successor in the Army High Command, and many other unsupportive or outright treacherous elements within the Reich’s circles of power. The German High Command became a nest of conspirators disloyal to the Fuehrer. This disloyalty is a contributing factor of German defeat down the road, but its negative effect was not yet critical in 1941.

Both dictators failed to achieve the proper balance between military loyalty and efficacy, and this translated into millions of deaths on both sides. Stalin should have been less brutal, and Hitler should have been more ruthless. In 1941 however, Stalin’s mistake had much more impact than Hitler’s.

Lastly, the Russians undervalued the competence of the German Army. They assumed complete ability to stop any German offensive before the Dnieper River, not realizing in its proper magnitude the one aspect that the Germans got especially right: the deployment of the most skillful army of modern times wielding an implacable method of waging operational war. Specifically, they failed to appreciate the decisive importance of the control of airspace in modern war. Like the boxers that find themselves face to face in the ring to contest the championship fight, the real surprise for Stalin and his Generals was not so much that the Germans attacked or even the timing, but the obvious skill of their foe that translated into an amazing fighting power. This is obvious when considering that one year after the invasion, in the 1942 campaign, the Germans once again demolished the Russian defenses despite significant numerical inferiority and the Russian’s knowledge that an attack was coming in the summer.

Stalin, for political reasons, needed to justify to his people the reason of the enormous initial success of the German offensive (and consequently the enormous failure of the Soviet government) and did so with the excuse of surprise: a treacherous attack of an evil foe over an innocent and peace-loving country. Although he meant to convince his uneducated populace, his argument also persuaded generations of western historians.

Establishing the relative power of opposing military units is not science though. Modern wargames do this all the time by studying what in fact, happened. To plan their future actions, both Germans and Soviets determined the relative quality of their armies using objective and subjective data, but the Soviets proved less conservative and were disturbingly surprised.

Stalin and the Soviet State, nevertheless, proved able to respond to their initial errors, starting with the formation of a more rational command structure. On 30 June 1941, the State Defense Committee (GKO) was instituted with power over all matters of state with Stalin himself as the chairman. Decisions of grand strategic significance were the responsibility of this committee. On 8 August 1941 the Supreme High Command, or Stavka, a military committee for strategic decisions with functions somewhat similar to a war ministry was appointed under the leadership of Stalin. The Soviet dictator, however, never became Army Supreme Commander. He could select whomever he saw fit as a member of the GKO, the Stavka or as Army Commander and he was sure they would do their utmost or risk their lives. By doing so, he could immerse himself in important army decisions or detach himself to analyze grand strategic matters. This allowed him to keep a grand strategic perspective during the war.

By contrast, Hitler became de facto Minister of War when he occupied the post of Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces (Oberster Befehlshaber der Wehrmacht) after von Blomberg’s dismissal, forcing him to view the war from a strategic, as opposed to a grand strategic vantage point. By the end of 1941, he would narrow his view even more, when he occupied the position of Supreme Army Commander (Oberbefehlhaber des Heeres), restricting his perspective to a strategic-operational level. This factor had a disastrous impact on the conduct of the war on the German side since the Fuhrer started a trend to spend scarce time controlling army operations in lieu of more decisive problems.

It is easy to find fault on decisions made at the time with the help of retrospection and thence, the world is full of armchair quarterbacks. The American army succinctly explains the conundrum: “the future confounds even the most rigorous attempts to accurately predict how it will unfold. Because the future is difficult to predict and understand, warfare often resembles a race between belligerents to correct the consequences of the mistaken beliefs with which they entered combat” . Later, we would be able to understand how each party reacted to correct its mistakes, but now we need to see how the Germans prepared for the invasion.