Military factories have the job of manufacturing the weapon designs coming from the research centers in copious quantities and quickly. Even the best designs have a very low impact in war if their introduction to battle is late or in small numbers. In the latter case, the enemy can assess the performance of these weapon systems at low cost and from this evaluation, it can develop timely countermeasures.

Production in massive quantities is a prerequisite for the formation of large well-equipped armies, for the replacement of losses caused by combat and for the creation of strategic reserves.

To perform this task, plants require raw materials, energy, trained labor, manufacturing equipment, tools, supplies, and communication networks (ports, airports, rivers, railroads, and roads) to move the raw materials in and move the finished products out.

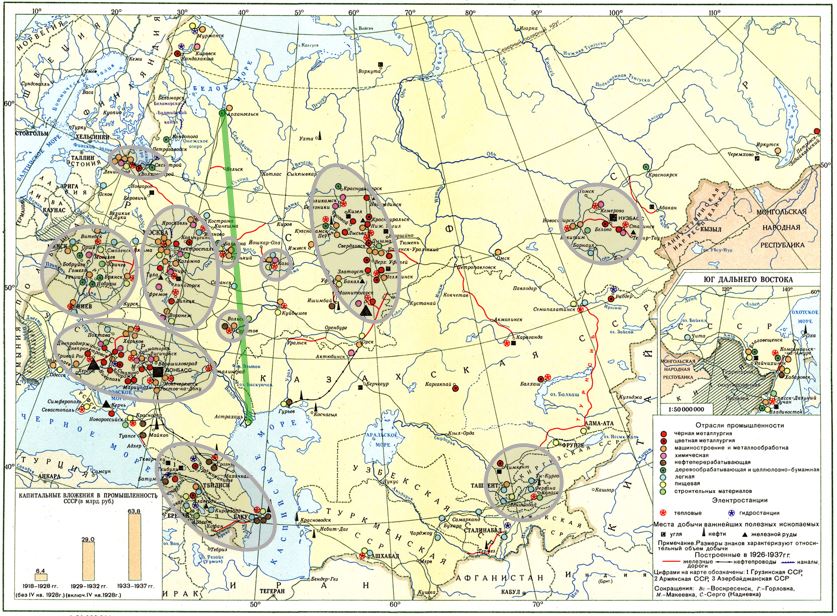

The decade-long effort of the Soviets to increase their industrial potential was unprecedented in terms of the sacrifices they paid and the results they reaped. German intelligence (and many historians afterward) failed to appreciate the extent of the astonishing enlargement and development of the munitions industry and its related supply infrastructure by the Russians. This was a most disturbing failure of the German army that had catastrophic consequences in 1941. The intelligence branch O Qu IV, subordinated to von Brauchitsch (through Halder), only gradually realized the extent of its erroneous appreciation. Between 1928 and 1940 Soviet machine-building and metallurgy grew more than eight times . Engineering high education centers jumped from 26 in 1927 to 150 in 1940 . By March 1941 the Soviet aeronautical industry employed 174,360 workers making it comparable to the 204,000 in Germany (1938) .

Since industrialization follows urbanization, and urbanization means larger population densities, most of the Soviet industrial expansion occurred in the heavily populated western provinces .

In 1941 the main industrial sites (see next map) were, not surprisingly, around the two largest cities: Moscow and Leningrad. Moscow assembled 50% of all the vehicles and machine tools in the country and 40% of all electrical equipment. It also had several aircraft factories. There were 475 major plants in the capital city . Leningrad had 520 factories and 780.000 workers and produced 20% of the machine tools, 91% of the hydro turbines, 82% of the turbine generators, and had among other firms, the Kirov works, the largest manufacturing plant in the country that produced the heavy KV-1 tanks. Leningrad by itself contributed 10% of the total Soviet industrial production . Together, both cities were responsible for more than one-fifth of the industrial production of the Soviet Union.

Other important industrial centers in western Russia were situated in Ukraine, namely in Kiev, the Soviet 3rd largest city (0.85 Million), Kharkov, the 4th (0.83 Million), Dnepropetrovsk (0.5 Million), Rostov-on-Don (0.51 Million), and around the Donets basin; and in the Caucasus, where 3 cities extracted oil in huge quantities: Baku (0.81 Million inhabitants, 5th largest city), Grozny (0.17 Million) and Maykop.

However, it was clear to the Soviet government that those centers would be vulnerable in case of war. New military factories were, therefore, built from scratch farther east on the Volga, in Stalingrad (0.45 Million population; artillery, tanks), Kuibyshev (0.39 Million; aircraft) and Gorky (0.64 million, tanks).

But this was still not enough and strategic industries started to emerge on and beyond the Urals, notably in Magnitogorsk (steel) , Nizhny Tagil (0.16 Million), Chelyabinsk (0.27 Million), and Sverdlovsk (0.43 Million), all three producing tanks. Other industrial centers arose even farther east in Omsk (tanks), Alma-Ata, and Novosibirsk in Siberia and even in the Vladivostok area (aircraft) near the Pacific .

Despite these precautions, roughly two-thirds of the Soviet industrial production was situated west of the line Arkhangelsk-Astrakhan (in green in the map) . O Qu IV correctly deduced its qualitative significance but not its quantitative importance.

Although the Soviet industrialization effort was gigantic in scope and it successfully reduced the large gap the Russian state had with Germany during the First World War , the fact remains that in June 1941 a predominantly industrial nation confronted a mostly agricultural one : in 1938, 20.2% of the total population of the USSR was urban while in Germany (1939) 31.6% was so .

Also, German farming productivity was significantly higher: every German farmer could feed 6.8 Germans (including himself) while a Soviet farmer could only feed 3.5 (including himself). This 96% productivity advantage on the German side , meant that even though the total workforce of Russia was twice as big as the German one (which is logical considering that the USSR had 170.6 million citizens, dwarfing the 76.1 million Germans ), the total workforce excluding food production, was remarkably similar between both countries: 32.5 million in the USSR vs 29.2 million in Germany .

Furthermore, the USSR’s landmass was 40 times the size of Germany , forcing the Russians to use twice the number of workers for transportation duties as the Germans. This reduced the available pool of workers for the Soviet industry. Overall, Germany had 16.5 Million workers for industry and construction, the most relevant segments for munition production, while the Russians had 16.1 Million (see table). This means that in theory, both states were equally capable of achieving the same output of weapons.

However, Germany had an advantage: Harrison provides data showing that the productivity of the Russian industrial worker was, at best, 80% of the German worker (and could be as low as 50%). The pertinent conclusion is that Germany had at least a 20% industrial advantage that should have resulted in considerably higher munition output . But that is not all, we also need to consider, that by the time of the German invasion, Germany could add to its industrial potential, that of the conquered countries (France, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, and the Low Countries) and also, that of allied nations (Italy, Romania, Hungary, and Finland).

As a result, Germany enjoyed at the onset of the invasion, a pronounced industrial lead that could be as high as 45% .

Once Germany invaded the USSR, its advantage increased even more, since the Soviet industrial sector received two massive blows: the reduction of the population (45% of the population was behind the German lines in 1941) and the disruption of the Soviet manufacturing capacity by the forced shutdown of thousands of factories for relocation to the east.

Just like in 1914, the larger Russian population was not decisive by itself, because the Russians still needed to arm new fighting formations and if Germany could place more tanks, aircraft, machine guns and artillery in the field of battle, their firepower would overwhelm the Red Army.

Altogether, Germany possessed a much greater manufacturing base that if properly managed, meant a significant armament production advantage. The potential of this benefit promised eventual victory.

Inexcusably, between mid-1940 to 1943, the German leadership squandered this strategic advantage.

During a war, the production of weapons tends to follow a Logistic Curve (see next figure) where initially there is rapid growth, followed by a slowing down until output cannot increase further. The munitions output in every category (tanks, aircraft, rifles, guns, ammunition, etc.) does not increase indefinitely because there is always a limiting factor present (usually a key raw material like steel or aluminum, but it can be labor, capital equipment or other factors).

However, an industry properly mobilized for war shall exhibit a steep production slope, reaching the maximum limit as soon as possible, while a poorly mobilized industry will grow slowly and will reach its maximum potential much later.

To exemplify, let’s take the case of what happened with the production of artillery guns in Germany and the Soviet Union: the maximum production the Soviets achieved during the war was 130.000 guns per year. In 1940, they manufactured 15.000 guns. The production increased very quickly: 41.000 in 1941, 128.000 in 1942, 130.000 in 1943 and 122.000 in 1944. This means that the Russians reached 32% of maximum capacity in 1941 and one year later they were at 98%. In comparison, the Germans achieved a maximum production output of 148.000 guns in 1944 and this was still increasing, while the Soviet’s output peaked from 1942. This indicates that the German defense-industrial complex was capable of outproducing Russia’s in the case of artillery guns, but they only did it when it was too late: in the critical year of 1941, the Germans only produced 22.000 guns, half the Soviet production and in 1942 they manufactured 41.000, only a third of Russian output.

Thus, the total gun production of the war was 513.000 in Russia and only 318.000 in Germany, despite the latter higher potential. Clearly, the Germans mobilized very slowly. Even by 1943, they had only achieved 50% of peak capacity. This slow mobilization meant that the Germans underutilized their larger industrial potential while the relatively backward Russians outproduced them by a wide margin.

The case of artillery guns is not the exception, but the rule. The same occurred in the case of armored fighting vehicles (AFVs), aircraft, and small arms.

Overall, in 1941, (the year of Barbarossa) the Soviet Industry beat Germany’s by a factor of 1.5-to-1 in combat aircraft, 1.5-to-1 in small arms, 1.7-to-1 in AFVs, 2-to-1 in artillery and 10-to-1 in mortars under the extremely demanding conditions of simultaneous evacuation, loss of population and with the handicap of starting with a smaller industrial base.

The enormous success of the Soviet Union, with an economic system usually believed to be inferior, begs the question: why did the German war mobilization founder so spectacularly?

The Russians indeed enjoyed a vast advantage in raw materials (oil, minerals, etc.) and they did not have to face maritime blockade, but this is not the reason of the difference: The Germans reached a higher level of production both absolutely and comparatively, later in the war when the blockade was tighter and when the US and British bombers were pummeling the German factories.

Barber and Harrison determined that the heavy focus by the Soviets in standardization to maximize production of a few designs was the difference. Germany was manufacturing too many dissimilar designs, and this was abnormally reducing output. This hypothesis is sound since in later years Germany rationalized the number of designs in production and increased substantially the output.

However, other major inefficiencies had an earlier solution. For instance, the excuses of German industrialists in the aeronautical sector, attributing low levels of production to limitations on aluminum proved largely unfounded: Erhard Milch’s audits confirmed the wasteful use of this metal. Furthermore, German aluminum production was at least double that of Russia in 1941 . Even more significant, Udet’s Luftwaffe production projections were badly planned. Milch later proved able to correct them .

After the invasion started, the USSR had the opportunity to import munitions from abroad. They did so in increasing numbers as the war went on, but in 1941 arms imports from the US and the UK were largely inconsequential. Only 82 artillery guns (0.15% of Soviet 1941 production), 648 tanks (12.14%), and 915 airplanes (10.26%) arrived during the Barbarossa period. Because of the late delivery, some of the equipment that arrived did not make it to the front in the first year of the war (i.e. only 115 of the 466 tanks manufactured in the UK did) . The value of the lend-lease imports during 1941 was 1.3% of the total all-war figure .

The conclusion is that the USSR outproduced Germany in 1941 owing to its efforts, without any significant external help, despite a smaller industrial sector, and in the face of the dreadful disadvantages caused by the invasion. This communist achievement is monumental.

The human factor likely played the greatest part in this success. From the (probably frightful) sacrifices of the Soviet worker to the skillful administration of all the industrial factors by the Soviet bureaucrats and leaders who despite errors, yielded better results than their German counterparts which were facing lesser challenges during the first year of the Russian campaign.

Military commanders do not have the expertise to lead this industrial task, although they do have a very important say in the matter (they place the requirements). Capable professionals with abundant expertise in production problems must carry out this job under the strong leadership of a very experienced economic minister. The latter, supported by the government head and cabinet, must allocate huge resources to build capacity while ruthlessly tackling bottlenecks. Once the factories are in operation, the minister(s) must prevent stagnation by ensuring productivity continues to increase by every means available, including identifying nagging problems and implementing innovative solutions. The government head and cabinet must dedicate considerable time to oversee this process because of its decisive importance. This is a grand strategic function with more weight than the conduct of battles in military campaigns.

Given the initial major advantages it enjoyed, the German leadership is guilty of lethargy of vast proportions in the industrial sphere. The poor intelligence picture presented by the army indeed contributed to overconfidence, but the mobilization of all economic, industrial, political, and financial resources to win this war demanded utmost urgency given the ghastly consequences of defeat .

To this date, many historians, and German apologists, including military officers, claim that the solution to overcome Soviet arms production advantage was the use of a strategic bomber capable of destroying Soviet industrial centers .

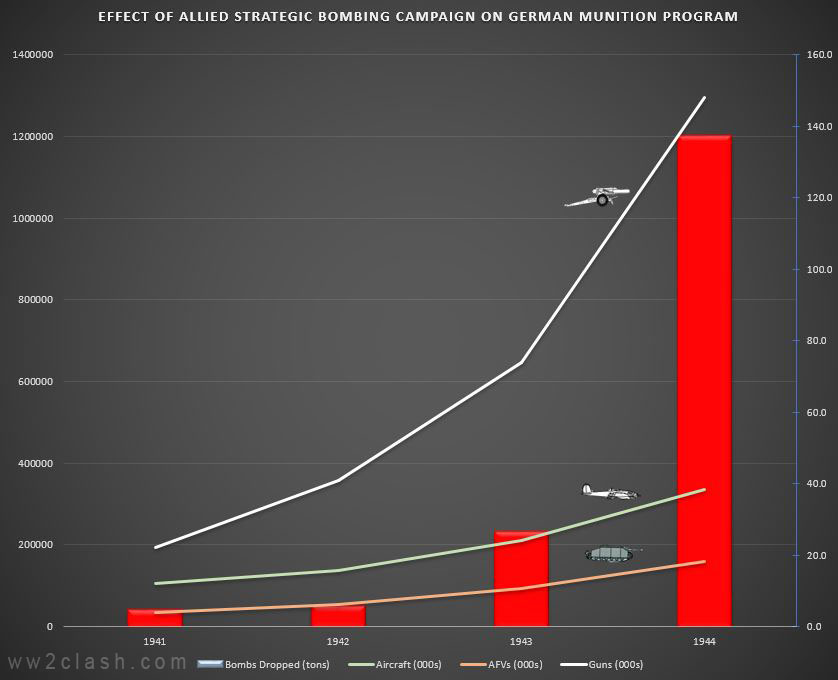

This is untrue. The Germans increased munition production substantially despite the massive bombing of their factories and there is no reason to think why the Russians could not have achieved a similar feat.

Although the United States and Great Britain spent a massive proportion of their national efforts on their bomber forces and succeeded in delivering every year an unprecedented tonnage of bombs on German towns and cities, the resilient Teutons increased armament production unrelentingly.

The next chart shows that during world war 2, there exists a relationship between bombing and production, but not what we would expect: this correlation suggests that the heavier the bombing the greater the production .

This does not mean that the Germans favored being bombed. It demonstrates, however, that other powerful factors more than offset the effects of massive aerial bombing, making it much less effective than even the most pessimistic of air theorist assumed.

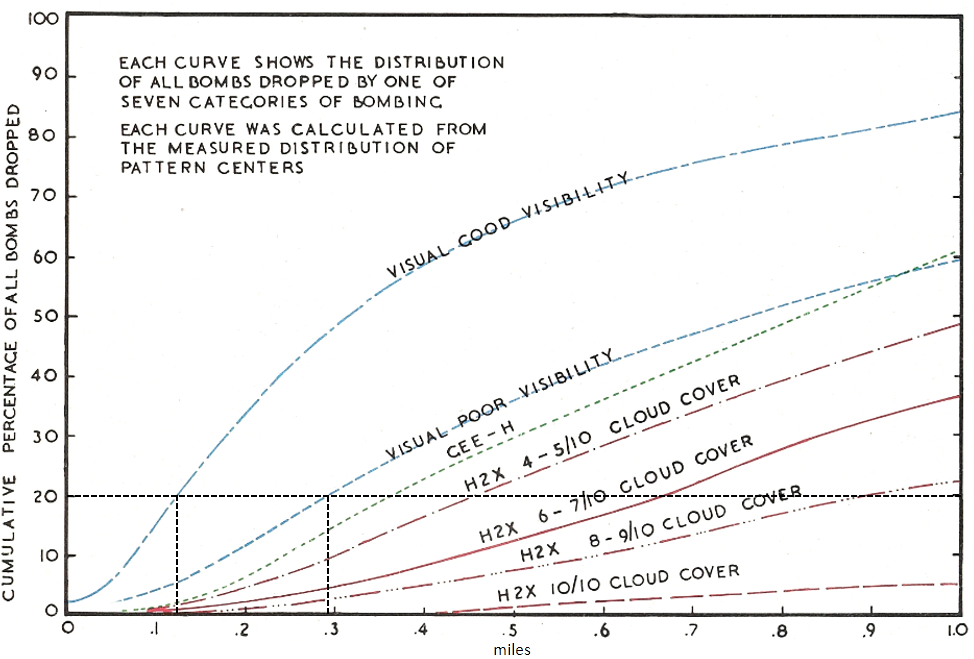

One factor was bombing precision.

As late as September-December 1944, fully 3 years after the launching of Barbarossa, most bombs released from high-altitude horizontal bombers were not hitting their targets, even by day .

Under these circumstances, the larger carrying capacity of heavy bomber formations was a critical requirement to increase the probability that at least some of them would hit the target.

Additionally, even when hit, industrial targets were tough to destroy. The scattering of factories proved to be an effective solution for the British as early as 1940. Air commanders also realized that it was much easier to wreck a building than to destroy the equipment inside, so production usually restarted much faster than thought possible.

If those difficulties were not enough, German strategic bombers with the range to attack factories in the Urals would still have to face enemy fighters. It was an easy matter to deploy Soviet fighters in airfields around this region . The Americans, using much-improved bombers with the latest technology in 1943, failed in their efforts to use self-protecting bomber formations and it was necessary to introduce long-range fighters to continue the offensive. Long-range fighters capable to escort heavy bombers became available only until the spring of 1944. The British never succeeded in introducing a long-range fighter and had to switch to night bombing whose accuracy was inadequate to do the job.

The summary is that even assuming that the Ural bomber was available in quantity in 1941, it is preposterous to conclude that the Germans would have overcome all the obstacles for the successful destruction of the Soviet Industry from the air in a reasonable time. The level of technology available in 1941-1942 made this goal impossible .

But the assumption that Germany could have constructed enough bombers to carry out a powerful sustained strategic campaign against the Soviet Union while at the same time deploying a tactical strike force for the Blitzkrieg lacks any substantive proof. In the period before the start of World War 2 and until the fall of France, Germany lacked the resources to support unrestricted rearmament. The need to import almost all raw materials and the scarcity of hard currency to pay for the imports placed a hard limit on the size of the German armed forces. This situation reached a crisis in January 1939, when it was necessary to implement a drastic reduction in the Wehrmacht allocations, including notably a 30% reduction in steel and 47% in aluminum . This translated into a fixed ceiling in the availability of these key raw materials for the production of airframes and engines.

Concurrently, the Luftwaffe was competing with the other services for resources. Its share of the Reich’s defense budget (and raw materials) was already as high as it could get .

Consequently, the Luftwaffe leaders had to carefully select the type of aircraft they needed and after careful consideration, they resolved that the force structure required to carry out the missions defined in the Air Field Manual 16 (that defined a predominantly tactical mission for the air force) consisted in 40% bombers, 30% fighters, 20% observation aircraft, and 10% transport aircraft.

How would this force structure have changed if the Luftwaffe had selected a strategic mission? Field Marshal Albert Kesselring indicated after the war, that even with a strategic mission, the proportion of fighters and observation aircraft would have remained approximately the same. He even accepted the possibility that an increase of long-range fighters could have been necessary to protect the long-range bombers .

With the aeronautical industry already working as rapidly as feasible, any engine (the key industrial bottleneck ) devoted to heavy bombers was an engine lost to the other sub-branches .

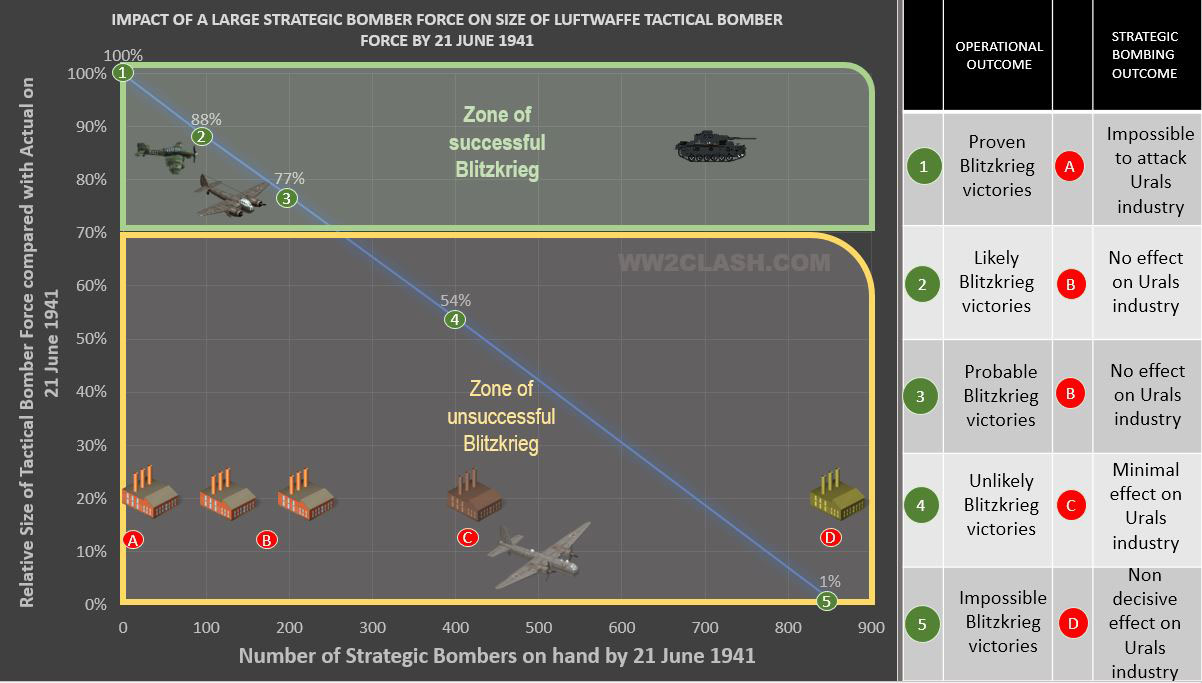

To quantify how the manufacture of heavy 4-engine bombers would have affected the production of single-engine and twin-engine tactical bombers and the possible impact in operations, a model was developed. The following picture illustrates the results of this model.

The horizontal axis represents the number of strategic bombers that theoretically could have been deployed by the Luftwaffe by the time of Barbarossa if the German had hastened its production, while the vertical axis shows how the size of the tactical bomber force would have been altered by doing so.

The vertical axis denotes a ratio that goes from 0% to 100%. Zero percent means that the tactical bomber force had to disappear to make space for the production of a certain number of strategic bombers.

A value of one hundred percent signifies that the tactical bomber force was not reduced at all and enjoyed the size it deployed on 21 June 1941.

The assumptions of the model, supported by research, are:

1. Engine production was the bottleneck

2. The proportion of recce aircraft stayed at 20%

3. The proportion of fighters stayed at 30%

4. Changing engine production to supply strategic bombers did not negatively impact its output

5. Engine production could not be increased further because of budgetary/raw material constraints

6. Tactical and Strategic bomber forces compete for the number of aero-engines produced

The benchmark case is what occurred factually: no heavy bombers present on 21 June 1941. This means that 100% of the tactical bomber force (number 1 in green in the chart) remained available for the Barbarossa operation (this force numbered 1.511 twin-engine bombers and 424 single-engine bombers ).

Under this scenario, evidence reveals that the size of such strike force was squarely in the zone of successful blitzkrieg operations. After all, a smaller force was enough to defeat Poland and also the Balkan States supported by Great Britain, and a similar force was sufficient to defeat France and its allies. Conversely, there were no strategic bombers. It was consequently impossible to launch a campaign against the Soviet industry in the Urals (letter A in red). The Soviet industry would remain unaffected.

If the Luftwaffe had manufactured 100 strategic bombers the magnitude of the strike force would have been reduced by 12% (number 2 in green). It is likely that this small reduction of tactical bombers would not have impaired the success of the Blitzkrieg. But one hundred heavy bombers would not have had any impact on the Russian munitions industry.

Why?

The Russian armament industry was roughly the same size as the German industry and using the USAAF as a yardstick, we know that by January 1944 the Americans had enough bombers to hit consistently the German industry with some effect . On that date, the USAAF could deploy 2.672 heavy bombers for operations .

One hundred bombers, however, represent only 3.7% of this USAAF strategic force. The effect of this small number of bombers would have been negligible (letter B in red). A similar result occurs with 200 bombers: the 7.5% relative size of the German strategic bomber force compared with the American yardstick is still insignificant (letter B in red), but the tactical bomber force size is now only 77%. This size is probably still sufficient for a Blitzkrieg, but the margin is not big (now only 1.160 twin-engine bombers and 326 single-engine bombers are available).

Once the long-range bomber force attains 400 bombers (15% of the American benchmark) it had sufficient strength to sporadically hit the Soviet industry on the Urals with force, but the effects would have been inconsequential. This is the size the USAAF had in January 1943 when it was still too weak to deliver serious setbacks to the Germans. Nevertheless, the effect on the tactical bomber force size would be dramatic: roughly half-the size it had in June 1941. This much-reduced strike force, in all likelihood, would have been completely insufficient for a successful Blitzkrieg.

The 400-size heavy strategic force yardstick is important because it indicates that a “compromise” Luftwaffe who had decided to pursue both strategies, tactical and strategic bombing simultaneously, would not have achieved good results with any, deeming this course of action ineffective.

What if the Luftwaffe had abandoned the tactical strike force concept altogether and decided to place all its efforts in building a strategic air force?

In this case, the tactical bomber force would not exist, preventing any Blitzkrieg. Instead, it would boast 850 heavy bombers ready to pounce the Soviet munition industry.

Unfortunately, the bomber force, now amounting to 32% of our yardstick, would have been able to achieve results comparable to the ones the Americans obtained in April 1943, (when they had this number of bombers). These were far from decisive. The Luftwaffe would have faced a long attrition campaign while the Wehrmacht would have to face an enormous enemy land army with scant air support.

We need to remember that no large-scale German offensive was ultimately successful during World War 2 without air support.

The conclusion is inescapable: Had the Luftwaffe been designed as a strategic air force this would have been the worst of the possible scenarios for the Germans because during the period 1939-1941 they would have found it impossible to heavily damage industrial targets, particularly in the USSR and they would have lacked the tactical strike force that made possible the smashing blitzkrieg victories. Even the victory over France would have been unthinkable. The Luftwaffe leaders correctly defined their air force mission and force structure. There was no mistake here.

Rather than pursuing an unviable attempt at strategic bombing, Germany should have made every effort to mobilize its munitions industry at the same rate as the Soviets proved capable of doing.

If they had done it, the increased production would have been sufficient to replace all losses and create significant reserves, creating a very difficult condition for the Soviets, who were losing equipment at a much higher rate than the Germans .

Given the low production rate of the aeronautical industry, the dispersion of the Luftwaffe strength to three fronts (Russia, Mediterranean and western) appears as a reckless move.

To defeat Russia, Germany had a window of opportunity that lasted from 1941 to the end of 1942 . After that, the combined potential of the Allies would become overwhelming.