Copious munition production needs trained crews in huge quantities to match man with weaponry and transform the output into strategic reserves suitable for combat. Otherwise, the additional production is only useful as replacement stocks (i.e. a lost tank can be immediately replaced to the surviving crew).

Training civilians to become tank commanders, pilots, riflemen, radio operators, mechanics, or the hundreds of different specializations necessitated in modern armies, involves more than teaching them how to use their equipment and weapons. They need to learn the tactics to survive and win. A fighter pilot, for example, needs to learn to fly his aircraft with proficiency and then how to operate as a team member in a fighter formation. The same is true in all army trades.

The required skill-set took as low as a four-month of instruction for a rifleman (plus a variable period of advanced training) to as much as 15 months for a German fighter pilot .

To make matters more complicated, war conditions change, and the training must adapt to it. Survivors acquire experience and they become more lethal against newcomers, so to increase the chances of survival of new soldiers, armies analyze enemy tactics and find ways to counteract them. Then, training centers teach these fresh solutions to recruits.

Soviet military training centers proved capable of instructing millions of reservists. By war’s eve, the Soviets boasted a 5.4 million soldier army with a pool of 14 million trained reservists . In 1938 a Soviet organization, Osoaviakhim, was training 3 million men per year and it had been doing so for more than a decade . This vast number of reservists conferred enormous depth to the Red Army: It could accept grievous losses and remain an effective force (The RKKA could lose the 3.3 million soldiers deployed in the western districts as many as 4.24 times and still keep its original strength)

The Versailles Treaty, by limiting the size of the German Army to 100.000 soldiers, ensured that for a decade the Germans were unable to train reservists causing them to face chronic shortages when they started to expand their army.

The German Armed forces deployed 3.5 million soldiers for Barbarossa and retained another 900.000 combatants in garrisons in the West and the Balkans plus only 321.000 replacements . This level of reservists only allowed moderate losses (10% loss-rate of initially deployed force), before the army started to lose its edge, causing the Wehrmacht to be brittle.

The level of training in the Red Army proved to be inferior to that of its foes for most of the war and this is a prominent factor that explains the favorable kill ratio the Germans enjoyed. This was particularly true in 1941. One reason for that appears to be a more professional stance of the German army rather than a lack of opportunities for the Russians. After all, the Russians trained reservists for a decade and there was ample time to fine-tune training while the Germans started later but developed more effective courses. Besides, both countries faced each other during the Spanish civil war and both fought wars with other nations during 1939 and 1940, giving them similar experience and opportunity to perfect doctrines and training .

The other reason, explained in more detail in a later chapter, is the effect of the Stalin purges (starting in 1937) that created a major dislocation in the Soviet command structure, impacting negatively the training of recruits .

Regardless, the number of reserves and training infrastructure allowed the Russians to raise copious quantities of new formations with just enough officers and training to maintain a minimum of fighting capability.

The Versailles Treaty, by limiting the size of the German Army to 100.000 soldiers, ensured that for a decade the Germans were unable to train reservists causing them to face chronic shortages when they started to expand their army.

In contrast, the Germans failed to substantially increase the pool of trained recruits for Barbarossa. Compared with increasing industrial production, the task of training soldiers, although daunting, seems less complicated. Training requires weapons, equipment, and vehicles , but they can be of a much more basic design that is easier to manufacture in massive quantities. Skilled instructors are the real bottleneck.

Germany had some significant untapped resources: there were thousands of available officers, mechanics, and specialists in the conquered territories, suitable as instructors for basic training (and even for specialized technical training in many cases). They remained unused for the most part.

Also, the possibility existed for a drastic redesign of the training courses to streamline them and reduce the number of hours. The Germans eventually did it, but only when they faced a crisis .

Thirdly, German leadership should have conducted a huge reorganization of labor since a man cannot be simultaneously in the army and the factory.

Men had to be in the front, therefore others: women, youngsters, and foreigners, should substitute for them. The Russians carried out a ruthless redirection of labor, increasing the number of women and youths in factories and boosting the daily working hours. They also used women in the army in non-fighting roles in 1941 but later, they even used them in certain fighting specializations (snipers, night bombers, fighters, and anti-aircraft artillery were the most common).

The Germans could have started this process forcefully after the defeat of France and they chose not to.

The shortage of proficiently trained reserves impacts harshly military campaigns. Air operations provide an enlightening example.

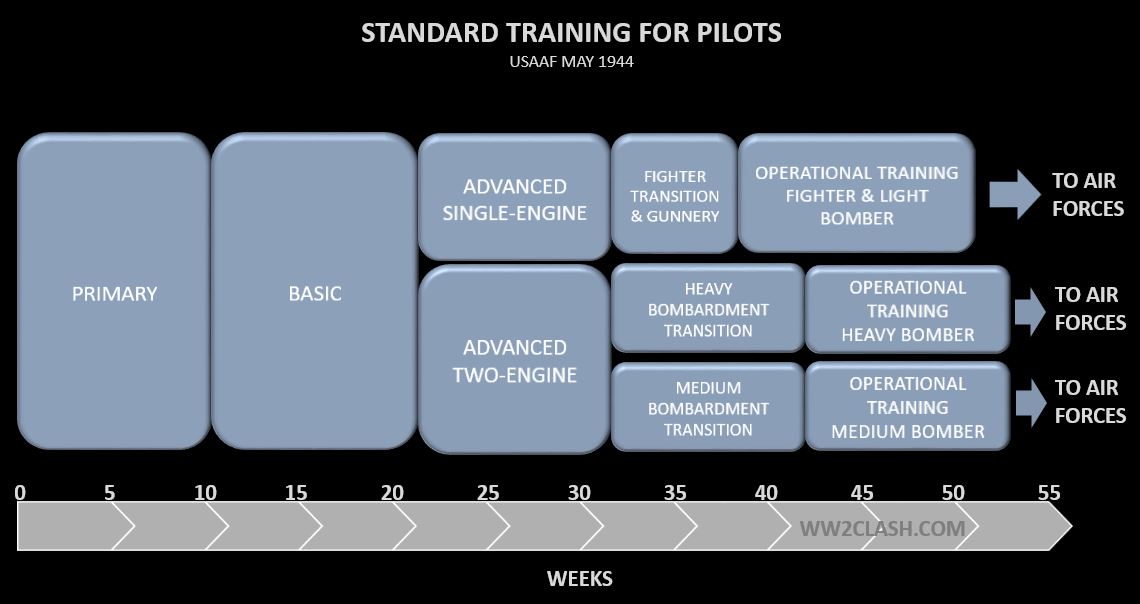

The next figure summarizes the duration of the different courses the USAAF developed to prepare its pilots. It took between 52 to 54 weeks to graduate fighter and bomber pilots. Evidence suggests that in 1941 the Luftwaffe courses were somewhat longer and VVS courses somewhat shorter, but not by much.

The air armies lost pilots as a result of combat and accidents. During Barbarossa, the Luftwaffe lost 1.13 fighters in accidents for each fighter lost in combat. For twin-engine bombers, the ratio was 0.56-to-1 . Knowing that it took the training organization around 1 year to train a pilot there would be an equilibrium if a pilot could last at least one year in the front, that is, by the time he became a casualty another pilot would take his place. A fighter pilot would fly around 200 missions per year if he was not killed or wounded .

To calculate how long a typical pilot would last, we need to know the loss rate as a percent of credited sorties. This data is not available for German and Soviet pilots, but we estimated a “normal” loss rate of 1.25% and a “heavy” loss rate of 6.52% using known USAAF rates in 1943, the first year of intense operations for the Americans in Europe .

It is remarkable to notice that even when the loss rate is only 1.25%, the average pilot only survived 55 missions and the whole unit is wiped out after 182 missions. That is, the unit does not survive the whole year. Observe that this is equivalent to a unit flying missions with 100 aircraft where 99 survive (and every 4 missions 98 survive). To the pilot, it appears that the mission-risk is low, but the accumulated loss tells us otherwise.

The loss rate of 6.52% is disastrous for the crews. The average pilot survives only 10 missions and the whole unit is destroyed after only 34 missions (about 2 months of operations).

Air forces (and armies in general) had 3 options:

• Select combat missions with very low loss rates (i.e. less than 1%)

• Reduce the number of missions (i.e. 50 or 100 instead of 200 per year)

• Create a huge pool of trained reserves in advance (i.e. 1000 trained pilots are kept in reserve for every 100 doing combat)